Sir Donald Sinden died in the early hours of Friday morning after a long struggle with prostate cancer. On Friday evening, the West End dimmed its lights in memory. Friends knew of his illness but he did not make it public and, though it had limited his activities in recent years, he continued to perform public duties until quite recently.

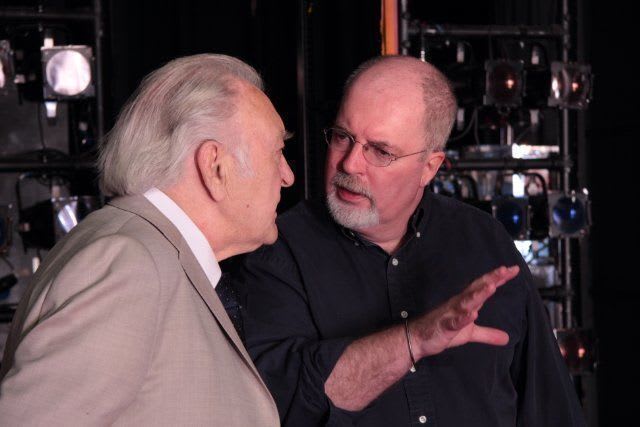

Only last year, he completed a series of documentaries about the history of 40 of London’s theatres, directed by his theatrical producer son Marc Sinden, which were issued as DVDs and then shown on Sky Television.

He also made a series of other recordings with Marc to preserve some of his other theatrical memories. They and his film and video work remain but never again are we going to hear that prodigiously plummy and immediately identifiable voice launching live into another familiar anecdote or commandingly querying, “who did you say you were?” when telephoning him at Rats’ Castle, his Kent residence since 1997.

Sir Donald may not have flourished a fedora and worn the legendary thespian‘s astrakhan but this was an actor chappie non pareil. And he knew it. Public appearances could sometimes verge on self-caricature, for Donald loved being the public Donald—and Sir Donald too.

Though he did not take kindly to a Spitting Image puppet presentation of him as a pompous “actor’s actor”, he did like playing to audience expectations. And of course theatre folk and audiences loved that—and him, not just for his long service to the profession but for himself, a man with an exceptionally generous spirit, always ready to help if something deserved it.

Born in Devon in 1923, he grew up in a Sussex village and it was in Brighton in 1941 that he made his first stage appearance at the amateur Little Theatre, a replacement for a cousin who had dropped out because he was called up. The following year, aged 19, he became professional with a company touring the south coast to entertain the troops.

Sinden’s inexperience was outweighed by his availability: colour blind and suffering from asthma, which had already upset his schooling, he was thought unfit for military service. As he put it, it wasn’t talent that got him the job but the lack of any other fellows. Only later did he go to drama school, two terms at Webber Douglas (now part of Central).

The end of the war saw him in rep at Leicester and in 1946 he joined the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre company, then being given new life under Sir Barry Jackson, playing roles including Arviragus in Cymbeline, Lorenzo in The Merchant and Paris in Peter Brook’s youth-centred Romeo and Juliet. After two seasons at Stratford he made his London debut as Aumerle in Richard II, then joined Bristol Old Vic.

In 1949, he got a small role in the West End in The Heiress with Ralph Richardson and Peggy Ashcroft. It was only nine lines but he didn’t miss one of its 644 performances. That set a record at Theatre Royal Haymarket, and the management marked it by presenting him with an engraved silver ashtray, which he proudly displayed when presenting that theatre’s history.

In 1952, the Rank Organisation offered a seven-year contract and his film career was launched with a leading role in The Cruel Sea getting star billing alongside Jack Hawkins. He soon became a favourite with film fans, especially in comedies such as Doctor in the House and its sequels, but there were serious movies too like Above Us the Waves, The Black Tent and Mogambo (directed by John Ford, whom he thought a bully).

Although he made well over 20 films, including one for Disney, he didn’t run off to Hollywood and when British cinema hit hard times in the 1960s he found his work in theatre back on stage.

By then, married with two children, he has said he had a tough time: auditioning for Peter Hall he was rejected, but he also reckoned that between that first job in 1942 and when he deliberately reduced his workload in 2008 he had no more than five weeks of unemployment. A long run in Guilty Party at the St Martin’s in 1961 put him back on his feet and was followed in 1963 by joining the RSC after all.

Donald made more than 50 television appearances, gathering a new generation of fans in series such as Two’s Company, paired with Elaine Stritch as her butler, in Never the Twain as antique dealer rival of Windsor Davies, and more recently as Sir Joseph Channing in Judge John Deed but he was not over keen on working in television. His first love was definitely theatre.

For more than six decades, Donald Sinden delighted us in an enormous range of roles. Whether as accomplished farceur, comic actor or at home in the classical repertoire he became a star figure in the theatrical firmament. A magnificent Malvolio, a definitive Benedick, a be-rouged Lord Foppington or a Scarlet Pimpernel, in tragedy as Lear or Othello, (which he found quite a challenge), a political Polonius or in Sheridan, Shaw, Chekhov or Coward there were many performances that will stick in the memory.

He gathered appropriate acknowledgement: Best Actor from the Evening Standard, SWET Actor of the Year, Broadway’s Drama Desk Special Award, nominations for Tony and BAFTA, the Freedom of the City of London, Honorary Degrees from the Universities of Leicester and Kent and in 1979 the award of CBE for services to theatre, followed in 1997 by a knighthood.

Those awards were not just for his work as an actor but also for his service to the professional in general and other bodies. As well as his record on the Council and as a Trustee for Equity, he served on the Arts Council, played a major role with the Royal Theatrical Fund and other theatre charities and in other fields served on committees for the National Trust, the BBC, the Royal Society of Arts and the V & A.

Donald had an abiding interest in theatre history and was a collector of theatrical ephemera that included pictures, playbills, props, stage jewellery and even furniture. He was Chairman of the British Theatre Museum Association, set up in 1957 by him and Laurence Irving (Sir Henry’s grandson) to collect material for a national museum of performance, beginning with Irving’s own archive. By 1963 they were open to the public with their own display space at Leighton House.

In collaboration with dance critic Richard Buckle’s Friends of the Museum of the Performing Arts, they pressured for a separate national theatre museum. In 1974 they eventually got government agreement, though it was not until 1987 that the Theatre Museum opened its doors in Covent Garden, under the umbrella of the V & A.

In 2006, when the Museum was threatened with closure due to lack of funds, objectors, me among them, came together under the name Guardians of the Theatre Museum to try to keep it open. It was a natural step to ask Sir Donald to be our figurehead.

On 1 April the following year, the presentation of the annual Theatre Book Prize, for which I was responsible, took place in the museum, its doors already officially already closed to the public. After welcoming guests, its director Geoffrey Marsh announced the removal of the collection back to the V & A before the Book Prize presentation. Sir Donald was in the audience. As soon as the winner been announced (by Daniel Radcliffe) and the award presented, I invited him to speak about the museum situation.

“I'm sure that when I was asked to come along this morning it was to lighten the proceedings slightly with a few odd quips,“ he said, “but I'm afraid that I am spitting mad about the Theatre Museum—the demise of—It is disgraceful!” and went on to ask for everyone’s support in efforts to raise the half a million needed to keep the museum open.

“We sweated away 50 years ago to get this place off the ground and then they can close it—just like that! Terrifying!” Donald was like a tiger defending its cub.

The Guardians didn’t win, but Sir Donald’s involvement was typical of his passionate commitment to what he cared about and their efforts made the V & A board take their theatre collection much more seriously, ensuring a much bigger profile when its new galleries eventually open in South Kensington in 2009.

Sir Donald always had time for those who shared his passions, for causes that needed his support. He had time to chat to the 12-year-old me who asked him for an autograph at Stratford, to address a lecture to theatre history enthusiasts, and not only to present the Theatre Book Prize when it moved on to its later venue at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane but to come each year—even if not well enough to do so, son Marc told me he wanted to be invited.

Perhaps his status sometimes made it difficult for people to approach him. One of the last occasions when I saw him at a function where he would later be getting up to make a short speech, he was sitting silent so I went over and joined him. A chair was rapidly vacated for me and immediately we were chatting like two old codgers.

I wasn’t a long-standing old friend but an acquaintance, just a face he recognized, but conversation always flowed whether ensconced in the Garrick Club or out among the public: a fund of anecdotes, of reminiscences as well as comment on current theatre.

An admirer of Oscar Wilde (he came to play the man himself as well as being in his plays), as a young man at a poetry reading in 1942, he met the elderly, impoverished Lord Alfred Douglas, Oscar’s Bosie. When Douglas died three years later, Donald attended his funeral—there was just one other mourner. That is typical perhaps of his behaviour, warm and loyal whoever you were.

Sir Donald Sinden was born on 9 October 1923 and died on 12 September 2014

YouTube and other sources will furnish samples of Sir Donald’s work but there is also an intriguing clip of a young Sinden showing off some of his theatre collection at home in Hampstead Garden Suburb together with his wife Diana, (who died in 2004) and sons Jeremy (died 1997) and Marc.