Get a PR Man Before you SPEAK!: He Who Wins Doesn’t Perspire

We live in a world of images, a world in which images can easily have a profound effect on our interpretation of words.

As Sanja Mitrović has pointed out in referring to her latest production SPEAK!, during the 1960 US presidential campaign, Richard Nixon sounded pretty good to the electorate on radio, but during the first presidential TV debate in history, he looked very uncomfortable with his sweat-beaded forehead and nervous gestures, especially as he was immediately juxtaposed to the super-cool on-screen persona of charismatic John F Kennedy. At that moment, the art of political rhetoric was transformed forever and Kennedy won.

Mitrović’s concept is absolutely brilliant in the way it combines political speech-making with the type of reality TV show in which the audience votes for the participant of their choice. On entering the auditorium we are given a small, hand-held device and are told to push a button to vote for the most convincing speaker in an 8-round contest between two orators, one male, and one female.

To the ancient Greeks, who invented both democracy and public relations, oratory was the means by which a speaker best conveyed their standpoint. Together, rhetoric and oratory amounted to the art of persuasion, which could equally amount to demagoguery—as it inevitably did. Even in ancient Greece, a politician could hire a speech writer and learn the art of persuasion.

Mitrović and Vaes are presenting us with those ancient arts in modern dress. As part of their research, they both took a course with a PR agency that trains politicians and professional speakers. This is a no-holds-barred fight to win.

The texts themselves are drawn from speeches made by politicians and other public figures over the course of the last 100-odd years, though we aren’t told the name of the original speaker or the context until afterwards. These speeches are drawn from across the political spectrum from Hitler to Obama.

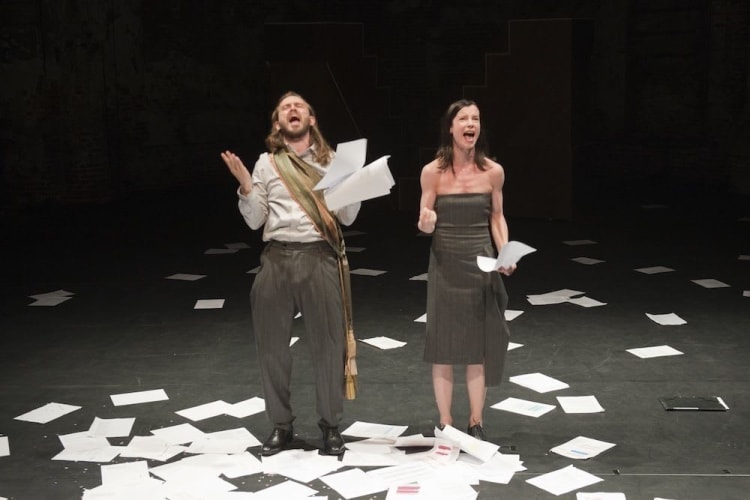

After each round, when we have cast our electronic vote, the winner (simply ‘woman’ or ‘man’) is revealed on an overhead screen with the percentages and the overall tally up to that point. There is some smugness or resentment on the part of the speakers, booing or cheering from the audience and at the end of the show the loser is excluded from the final applause.

The competition between Mitrović and her collaborator Geert Vaes is genuine. Mitrović might win on one evening and Vaes on another. During the show itself, the reactions from the audience egg them on to step up the passion or use more dirty tricks to gain the rhetorical edge in the game of persuasion.

This is fun; it really is engaging, but it also has a sharp edge. It throws up a wide range of questions about the choices we make in life, our responsibilities, and the responsibility to make democracy genuinely ‘the rule of the people (the demos)’, by voting at elections and making informed choices.

Do we vote? Why? Who do we want to win? Why? Are we voting for what they say or how they say it? Are we attracted by the way they look? Are we influenced because the woman is sexy or the man looks strong? Do we personally identify more with a woman or a man? Is the one who is calm and collected sincere, or the one who gesticulates passionately? Is the desire to win at all costs a sign of strength, a quality to be admired?

This show is definitely entertaining but it also generates doubts about the way we make important choices in life, who we trust, what ideologies we are willing to subscribe to.

Mitrović has cleverly added extra layers of complexity that make those decisions more difficult. We have to vote when a green light appears. We have to choose in a hurry, and surrounded by other voters we are under pressure to press a button. Can we make up our minds that quickly? Do we dare not to vote at all? This is a very modern dilemma.

And then there are the texts themselves. They tend to deal mostly in abstractions, words like freedom, hope, independence, progress, identity and citizenship abound. They make appeals to our sense of values, or our moral outrage, our better judgement or our desires for a better world, a prosperous future, for a break with the past, but out of context it’s difficult to know whether the speaker is appealing to our sense of solidarity for values and creeds to which we would genuinely subscribe.

We search for signposts that will show us how to interpret the words, but it’s obvious that for the most part politicians play safe when it comes to rhetoric; they stick to abstractions. And that’s why the oratory and the surface appearances become so crucial in our decision-making process.

There are further onslaughts on our decision-making as the speakers start to manipulate our sympathies by utilising relationships to space: speaking from a higher platform, upstage or downstage, trying to dislodge or disrupt the other speaker. The development puts us increasingly under pressure and I eventually gave up voting, because I liked neither of the speakers, nor what they had to say.

Mitrović started singing "Happy Birthday to You". At first I thought it was a joke, a parody of Marilyn Monroe singing for JFK, but when she continued, using reverb for her voice, sprinkling confetti, transforming the lyrics into Happy Birthday to Us, continuing with that single irritating phrase, I found that I wanted to vote for the man trying to take the microphone from her, the one who went on to speak of the triumph of independence, the first African country to become independent, and that sounded about right: the silly, repetitive triviality juxtaposed to a genuine politician striving for the liberty and prosperity of his people.

And then he started to talk about God! I don’t want to vote for anyone who puts God in the driving seat and I don’t want to vote for facile frivolity, so do I compromise or do I simply withdraw my vote; does that mean that have I been denied my democratic right to vote? Or is democracy itself a sham?

During subsequent rounds, the speakers seemed to be increasingly validating a freedom that could only be won through violence. I couldn’t vote for these people either. The noise of bombs falling and machine gun fire covered the rhetoric, even though, as it transpired later, the war speeches came as much from Winston Churchill and Franklin D Roosevelt as from Hitler and Saddam Hussein. The voting machines lay in laps as more people stopped voting, but many others continued pushing the buttons.

Sanja Mitrović was born in Serbia, and having experienced the latest war in the Balkans, including the bombing of Belgrade, probably has more reason that most of us to be sceptical about the way politicians, with the help of their media and public relations advisers, can become demagogues vying with each other for power through the popular vote.

On the other hand, having lived and worked in The Netherlands for several years, she must also understand the failure of Western democracy, the low turnout for elections, and the encroachment of popularist demagogues here too. SPEAK! exhibits a willingness to address the issues head on, but with a concept that reveals us to ourselves.

So, what conclusions can we draw from this invitation to join in the rhetoric and oratory of our own democratic processes? Mitrović has created a superb event, a piece of theatre that blends fiction with reality so seamlessly that it both entertains and manipulates our sensibilities.

Vaes and Mitrović are superb performers. The simple but functional set and lighting worked very effectively, especially in the stylishly dilapidated space of Les Brigittines chapel.

I sincerely hope that this show comes to a venue near you. Everyone should see it. At a time when our political system is looking increasingly bankrupt, it seems to me that voting for one party or another, or the lesser of two evils, is going to change nothing. As Tony Judt said: ‘What comes next?’

Whatever comes next in this age of transition it’s up to us all to play an active role in creating a better world. Speak! is the type of theatre that makes a positive contribution to shaping that transition.