H, An Incident: music theatre with a Russian dissident, an Icelandic choir and an orchestra of disappeared musicians

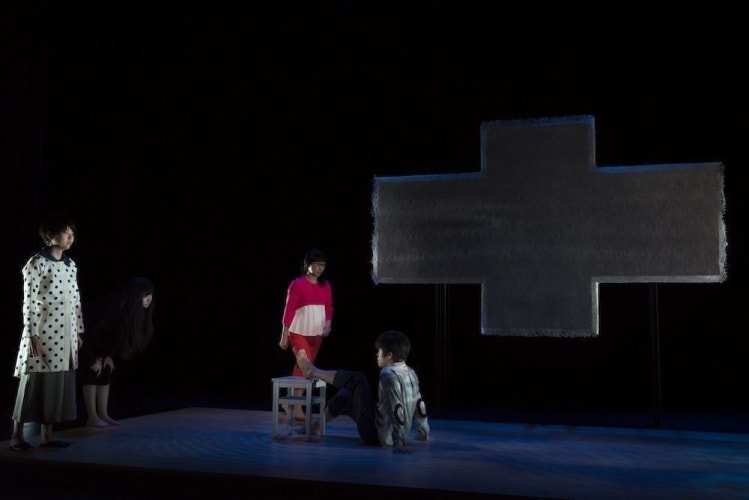

Kris Verdonck studied visual arts, architecture and theatre, which probably accounts for his ability to blend stunning onstage images, profoundly resonant, with performances that draw us deeply into a fictional world. A finely-tuned pacing keeps us there. The latest show, his first piece of music theatre, based on the work of Daniil Harms, is no exception.

Daniil Harms has often been referred to as the Russian Kafka or Beckett. He had close ties with the Futurists and was a good friend of the abstract painter Malevich at a time when the Soviet party line on art stipulated rigid adherence to the norms of Social Realism.

As a non-conformist and founder of the group Oberiu (Association for Real Art), Harms was sentenced several times to imprisonment and internal exile. He was arrested for treason and declared mad by the authorities in 1941, and died of starvation a year later in a ward for psychiatric patients in a Leningrad prison while the city was besieged by the German army. Harms earned the dual honour of being a victim of both the Stalinist purges and the Nazis. It is probably an irony he would have enjoyed.

H, An Incident is based on Harms’s work and life, but also the world in which he lived, one in which people simply disappeared without a trace and most lived in fear of the secret police and their collaborators. Nonetheless, Harms was a funny man, who loved to make his friends laugh with jokes, irrational poetry, non-linear theatre pieces, displays of ‘decadent’ behaviour, dressing up as Sherlock Holmes, and rolling his eyes up into his head. He created for himself the persona of the English dandy, often used the name Kharms (harm + k = charm) and worked from a belief entirely at variance with Social Realism, namely that art should be free from the rules and logic of contemporary society.

H, An Incident bears the hallmark of a tribute; Harms once wrote in a poem: ‘I was lost in the woods. If you meet me, please tell a friend’. Kris Verdonck, as he explained in his post-show talk, has set out to do just that. We, the audience, are the friends who should know about Harms life and work because it is relevant to our own.

In response the absurdity of the society he lived in, Harms work is rich in absurd humour, black and cruel like a Monty Python sketch. For example, there is the sweetly childlike blond gymnast who smiles angelically while recounting nasty deeds, delighting in blood and cruelty.

A man in an orange velour lion suit with shaggy mane and chest bounds around the stage enthusiastically, trying hard to be entertaining, too hard—as if his survival depends on it (perhaps he will end up in the Zoological Institute for Extinct Species rather than a gulag).

There is a woman on roller skates who keeps disappearing into a shopping bag on wheels, so that only the white skating boots and wheels can be seen: wheels below, wheels above. This is a particularly rich image, plain good fun, but with a bite. She also managed to turn the bag on its side and skate while most of her body was contained in the bag. A lady in a smart grey suit is desperate to sell a cucumber. Harms himself crosses the stage dressed as Sherlock Holmes. This is all so deliciously absurd, but it has a razor sharp wit.

As a central, recurrent image, there is the cleaning lady who puts her hand in her bucket with the cleaning fluid and howls with pain. She drinks cleaning fluid directly from a plastic can and howls again, stopping from time to time while cleaning the floor on hands and knees to howl, long, anguished howls of pain from deep within, like the cry of a woman in childbirth.

Perhaps, the bump under her jacket is a reference to this; she is pregnant. Perhaps, these are symbolically the birth pangs of art in the making. At the very beginning, a figure I presume to be Harms himself, tall and gaunt, clad only in a vest and underpants, kneels besides her with his hand in the bucket too. They are both wearing rubber gloves and stare out at the audience. This scenario is rich in potential meanings, many unpleasant, yet one can’t help but laugh at the absurdity of it while also admiring an actress who can howl like a banshee.

The music is provided by a ghostly orchestra, the instruments gliding around the stage like robots, the musicians having disappeared, or become ‘the disappeared’. It is a dual image; the instruments are moved by robotic technology and take on some humanlike qualities with small purposeful, sometimes sinister movements. I could have sworn that the tubas were watching us.

Like Monty Python, these scenes have no beginning, middle and end, no punchline, flowing seamless into each other. They are also Pythonesque in their repetition, returning time and again, in different configurations, as we try to fit the puzzle together and make sense of it all. Like Monty Python, the point is, there is no point. Harms lived in a world that was simply bizarre, so he made a joke about it. His work isn’t absurdist at all. It is a humorous depiction of the reality in which he lived.

He was just 37 years old when he died. He wrote popular children’s books for a living, but only two poems from his work for adults—short stories, plays, poems—had been published prior to his death. He was forgotten by all but a few friends who started spreading manuscripts in samizdat form in the ‘60s and ‘70s, but had to wait until the ‘80s and Gorbatchev’s perestroika to assemble the manuscripts together for archiving and publication.

My personal acquaintance with Harms’s work first came about through the production, by Théâtre de Complicité, of Out of a House Walked a Man, which opened on the Littleton stage at the Royal National Theatre in London in 1994 with Jos Houben as the man and Kathryn Hunter as the landlady who refused to leave his side even though she was dead. It was a production that did justice to Harms work with strong images that remain etched in my memory twenty years later.

Verdonck has also chosen to create a performance with strong, resonant images and intense physicality. The cast are clad in respectable, noncommittal grey suits, with waisted jackets and flaired skirts for the women. They don accoutrements to create characters—simple things like an apron, red wellington boots. It is a superb example of an ensemble cast filling the stage with abundance.

At one point, they fight each other in a sumptuously staged, free-for-all scrum, biting, slapping, punching, gouging, kicking and stomping even when the opponent is down. This really is a rumble reminiscent once again of Monty Python—remember the absurd scenes with men dressed as respectable, middle-class housewives with handbags fighting in the mud?

But here there is no slapstick. Harms thought that adults were childish and always fighting and yet he could still turn this into a joke. And these people, dressed like smart office workers, are very much our 21st century contemporaries. That is the point after all. The veneer of civilisation is wafer thin.

Harms’s contemporaries lived in fear, under pressure to conform and to spy on each other, to collaborate with the authorities in betraying friends and family. Individualism was a crime in a society that strove for a collective personality and a communal lifestyle. Many committed suicide or went mad. So, can we relax and enjoy the show because we are not living in a Stalinist dictatorship? Or has the nature and governance of our daily lives and the threat of a ‘gulag’ been adapted for our times?

As Verdonck points out, at present we live with technologies that are compromising our privacy and individual freedoms. Surveillance cameras watch our moves in public places; in private our electronic gadgets collect data that will be used to persuade us to buy more products, to conform to the personality of the model consumer. Maybe, those tubas really were watching us.

Another aspect of our contemporary life that is reflected in H, An Incident lies in the degradation of social ties and mutual trust as the neoliberal logic of continuous growth forces us to accept a deleterious competitiveness between corporations and nations and competition as a personal ethos.

While these contemporary agents of control might be more cleverly concealed than the KGB, the Komsomol and the Communist Youth movement of Harms epoch, the individual is now observed and exhorted to conform through our addiction to technology and the new media. We buy the same products, watch the same movies and TV, and talk about the same news (and, in the UK, soap operas). And we still believe we are individuals. Are we really adults and individuals or childish and cartoonesque?

Is it possible to think about alternatives? Can we imagine alternatives to the advanced capitalism that promotes so much fear? The questions are legion.

Harms dealt with this overarching control by creating a type of dynamic dissociation in his work—images with layers of potential meaning that break with conformity and a stereotypical closure of meaning. Verdonck and his cast have welded these into forceful images, buzzing with electric energy. The characters sing, shout, howl, fight, skate and dance with gusto, rushing at life with a positive force. The cast gives 120% while maintaining a pace that allows us to enjoy the irony.

The final musical number is a parody of the type of rousing propaganda routine found in musical entertainment from the Soviet era. The characters in Verdonck’s song and dance routine are cleaners with mops and brooms. It is performed to perfection, sublimely funny and if a slogan were necessary it could easily have been: cleaners of the world unite; you have nothing to lose but your mop and bucket.

Harms would love it.