Every now and again, it’s important for theatre-goers to see a canonical play, if only to ascertain whether or not it deserves to remain canonical.

After a difficult early history, A Doll’s House eventually became one of the most performed plays in the Western world. Those who, like me, experience it live for the first time in Rachel O’Riordan’s production of the Simon Stephens adaptation will be in no doubt as to its continuing worth.

The action centres around Nora Helmer, an apparently loving wife and mother. It quickly emerges that, several years before, she took illegal measures to secure a loan in order to protect the health of her husband, Torvald, then a struggling lawyer, now a successful banker. Now, she is being threatened with exposure and disgrace by the widely disliked money-lender Krogstad. The question of whether her marriage will survive is resolved in an unexpected manner.

When we first encounter her, Nora comes across as a flighty, fragile overgrown schoolgirl, and her husband frequently refers to her using “bird” metaphors. Kenny Miller’s set, while not being so unsubtle as to resemble a gilded cage, certainly suggests one, with its vertical lines and high ceilings. Simon Slater's music subtly suggests that there may be trouble ahead.

Leila Crerar has been gifted with one of the most coveted but difficult roles in theatre. Her Nora is all childish flutteriness at first, before the turn-on-a-sixpence mood swings become evident, prompting uneasy audience laughter.

She then has to metamorphose from a girl who attempts to solve her problems through intrigue and manipulation into a woman who realises that this is all pointless, and that her profound discontent has something other than money or social convention at its root. The fact that we remain on her side throughout is a testament both to both her skill at appearing guileless and the script’s acuteness.

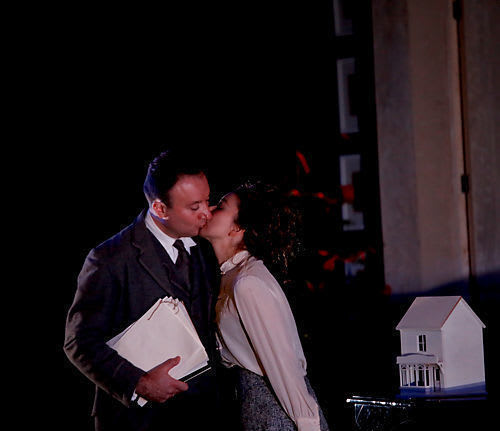

Alex Blake is affecting as the husband who thrives on Nora’s immaturity, his only crimes being complacency and conventionality. As with each character, though, there is a darkness not too far below the surface.

This is especially evident with Paul McEwan’s Doctor Rank, the family friend whose playful philosophising and shameless flirting mask his despair at the tragic family curse which is slowly destroying him. The Helmers' misfortunes are, to some extent, of their own making—his is not.

As we witness Nora journeying towards one kind of freedom, her returning friend Kristine (played by Kelly Williams) seeks to find herself by travelling in the opposite direction. We discover her painful history with Robert Vernon’s Krogstad; and he himself comes across as more victim than villain, his blackmailing of Nora seeming almost reasonable. Even Francine Morgan’s Anna, the family nanny, is dealing with the consequences of having broken the rules in a former life.

Ibsen refused to claim credit for creating a pioneering feminist drama—A Doll’s House is about the need for self-actualisation, written at a point in history when such a thing was denied to most members of most societies. This is a gripping production of a remarkably prescient play.