A rich subject for ballet, however one slices it, Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire is given a dynamic dance drama remake by an interesting duo: the international choreographer Annabelle Lopez Ochoa—whose first time narrative ballet this is, a huge undertaking—is supported by the vastly experienced director Nancy Meckler of Shared Experience theatre company’s unique stagecraft fame.

Indeed, Meckler spells out in the programme synopsis her revision of the play, her emphasis on the battle of the sexes, on the early cause of Blanche’s fragile grasp on reality in the gritty raw city of New Orleans, and it is her striking stage pictures which add drama to the dance—the inevitably of Blanche’s fall, the moth flying too close to the flame of desire.

All the main protagonists fly too close to the flame: Stella in her physical attachment in spite of an abusive marriage, Stanley in his destructive possessive demands, Mitch (Adam Blyde) and Blanche in their last grasp at a dream, and Alan, Blanche’s young husband, in his ambivalent sexuality. Suddenly, Last Summer and Montgomery Clift—Victor Zarallo’s Alan even looks like Clift—come to mind.

Echoes of echoes signify and stimulate connections: Blanche’s long white gloves and hat symbols of propriety and modesty; the Mexican flower seller dressed in black, who replicates till the stage is filled with them, red flowers in their mouths, sellers of flowers for the dead, resurrecting Federico Lorca imagery.

A bold undertaking, a Streetcar without the eloquent words—their poetry and music, which elicit such a depth of emotion and empathy from the reader—two hours of cabaret without the songs, though song there is—Ella Fitzgerald singing It’s Only a Paper Moon a haunting refrain.

Peter Salem’s score, performed by a live orchestra conducted by Martin Yates, waltzes, tangos, jive, New Orleans jazz, big band sound, snatches of a horn blowing the blues, familiar jukebox tunes ricocheting, abstract mood soundscape, has to draw out the meaning of the text, the cruel scornful prejudiced times, the yearning, and the gut-wrenching pity of it all, as well as drive the dance.

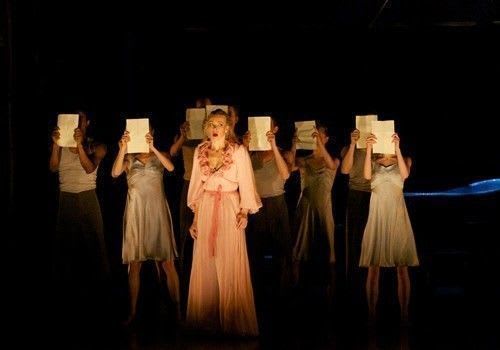

The ultimate onus is on the dancers, and here there is excellence. Estonian soloist, Eve Mutso, tall, elegant, leggy, superiority on pointes, has to command the centre as an actor dancer. In pale wafty white dress, and deep rose pink negligee and ball gown she stands out against the pale blue shifts of the corps, and the casual suits of the men.

Principal Sophie Martin brings a sensual intensity to the role of Stella, matched by principal Tama Barry as her burly brute caveman of a husband Kowalski, whose idea of love making is taking what he wants by force, be it his wife or her sexy siren sister. After his rape of Blanche—he’s the boss man—he swaggers off in boxer shorts and a boxer’s short dressing gown.

In fact, the athletic gymnastic expressive dancing can’t be faulted. The choreography is variable, with some dazzling and demanding duets, at times West Side Story and Guys and Dolls musical theatre (the men’s bowling alley competition) with high kicks, big numbers, a bit Hermes Pan and Gene Kelly, which fits the period bill.

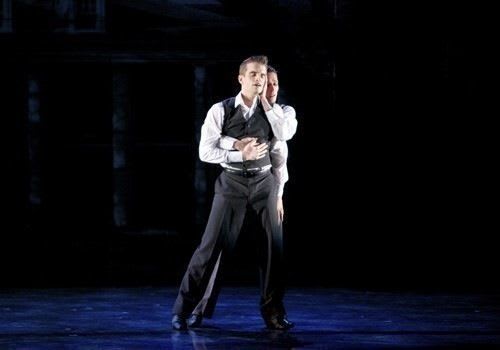

But it is Victor Zarallo, the young man whose suicide Blanche caused by her rejection of him on her wedding night after finding him with a man, who stays in my mind as much as he does haunting Blanche’s. And Luke Ahmet as his lover isn’t bad either in their tender duets.

Some set pieces are, naturally, more striking than others: Blanche’s splintering mind represented by six dancers all stretching towards that bare light bulb which turns into twenty-eight bare bulb stars in the sky; the dance in the bath tub with the men Blanche picks up; the damning letter setting off malicious gossip; Stella and Stanley’s passionate coupling.

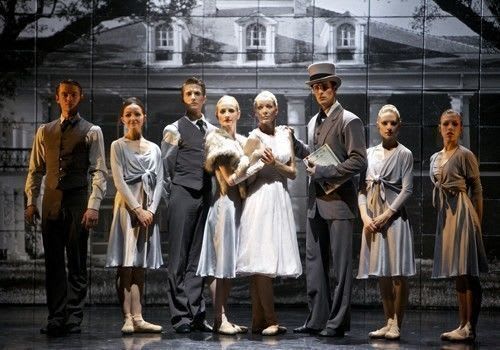

Nancy Meckler unpacks and explores the smaller details, the underpinnings of the tragedy, the psychology and sociology, whilst Annabelle Lopez Ochoa gives them life. Niki Turner’s costumes and set design are outstanding: clever use of crates the defining feature. A back wall with projection of antebellum white house disintegrates, crumbles—it is made of humble crates, their ruined heaps becoming a city skyline, basic beds, stage, tables, chairs, a jetty.

It is apparent an enormous collective creative effort has gone into the undertaking of such a challenging project, the hand of a feminist theatrical director giving a dramatic structural framework to the discipline of dance, a memory music box, a floorshow of borrowed emotions.

Having opened in Glasgow, visited Edinburgh and London, Scottish Ballet continues to Aberdeen, Inverness, and Belfast in May.