Wayne McGregor Random Dance / Candoco Dance Company / Hofesh Shechter Company Triple Bill: : FAR / Set and Reset/Reset / The Art of Not Looking Back

2-3 February 2012

Russell Maliphant Company The Rodin Project

5 February 2012

According to the press release, 2-5 February there were some 300 delegates from across the UK and the globe in London for the biennial British dance showcase. Supported by Arts Council, British Council and National Dance Network Initiative, British Dance Edition London 2012 had about 35 companies showing off their wares.

Produced by the London Consortium of the Dance Umbrella, East London Dance, Greenwich Dance, ROH, Sadler’s Wells, The South Bank Centre, The Place and Trinity Laban mainly for people in the business, it wasn’t all behind closed doors.

Some shows were open to the lucky public. As well as these reviewed here, there was also a double bill of Richard Alston Dance Company’s new Unfinished Business and the National Dance Company Wales in Stephen Petronio’s By Singing Light for one night only at the South Bank.

Tickets were at a premium at Sadler’s Wells for the Wayne McGregor Random Dance, Candoco Dance Company, Hofesh Shechter Company Triple Bill, and for Russell Maliphant’s new work, The Rodin Project.

Wayne McGregor’s familiar fast, arched, and arch, dance vocabulary was performed superbly by his company, the ten dancers thoroughbreds in perfect dressage. ‘Inspired by the controversial Age of Enlightenment and by the 18th century French philosopher Diderot's very first set of encyclopaedia, FAR mines an era that first placed a body in question’…

That may be McGregor’s inquisitive intellectual starting point, but the result is futuristic. Against Lucy Carter’s computer lighting grid backscreen (set by rAndom International), the dancers are Muybridge specimens reincarnated for the electronic age.

Four heralds with flaming torches transcend eras, but the dancers in nude costumes fire like computer-controlled electrons. To Ben Frost’s spiky music, these interstellar spiky creatures flit, pleat and unfold, from primordial forms to Paolozzi Newtonian, in unstable distortions, the old and the new commingling.

An exploration of space, of galaxies, the dancers no more than the smoke clouds that drift across the stage—is there some cognitive plan? Patterns, regular and irregular, repeat to the point of hypnotic overload, and dancers moves jar in multi-jointed deformed display. Is this tension, collusion or conflict, or McGregor testing the limits?

Where McGregor distorts bodies, Candoco Dance Company, comprised of disabled and non-disabled dancers, proves that anyone can dance, that disabilities can grace movement display. One reads that Parkinson’s sufferers improve with dancing. We should all be dancing—there are no restrictions only those we put on ourselves. Isn’t that wonderful?

And the Candoco dancers are wonderful in this well-chosen revival of Trisha Brown Dance Company’s 1983 Set and Reset/Reset. In grey chiffon costumes, which complement the backcloth grey canvases of geometric design, originally by Robert Rauschenberg, reconstructed by Celeste Dandeker (costume), and David Lock (set), they waft gently, in easy loose-limbed style, all pendulum and propeller arms, to Laurie Anderson’s repetitive score. Joyful in movement, dreamy, breezy, lovely, it suits them down to the ground.

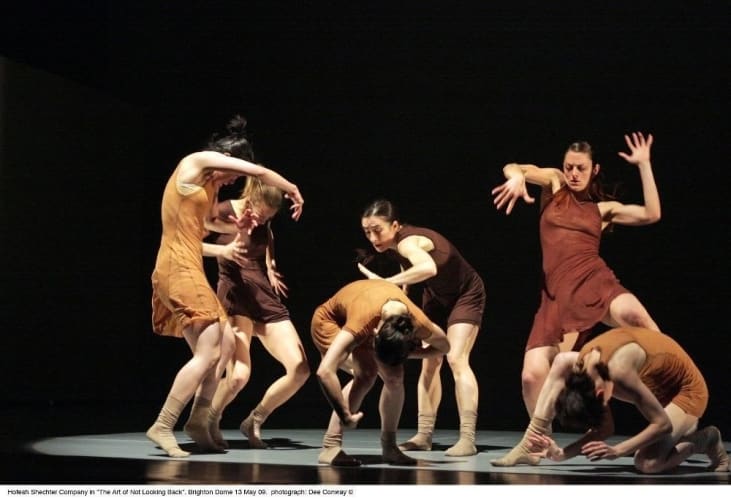

Hofesh Shechter’s The Art of Not Looking Back (a bitterly ironic title), made for the six female dancers of his company, commissioned by the Brighton Festival in 2009, bares his disabled psyche. No need for the psychiatrist’s couch when you can have dance therapy…

The score a mix of his voice, screaming, babbling autobiographical details, Bach, John Zorn’s Litany IV, and Nitin Sawhney’s (metaphorical?) Fragile Wind, it is moving, and unrelenting. As tough as his male dancers, the choreography as brutally physical, clutching at the air, the hunched women take on tragic proportions.

Under Lee Curran’s mood-setting hazy sepia, white, and then blood red lighting, they dance together holding hands in line and apart, in private and collective trauma, elbows in the ribs, knees in the groin, self-lacerating, this is a rebirthing, and an angry condemnation of both mother and motherland.

Dance as psychodrama: an unforgiving stance against the mother who abandoned him aged two, sears the soul. She is nothing to him. A wounded heart, his self-pitying scream brings little solace in an indifferent world. The dancers Sita Ostheimer, Maeva Berthelot, Winifred Burnet-Smith, Karima El Amrani, Yeji Kim, and Hannah Shepherd are terrific.

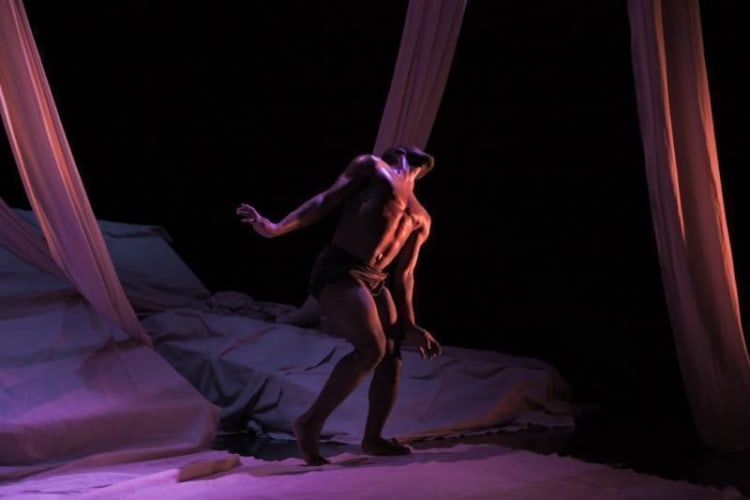

Inspired by the works of Auguste Rodin. Russell Maliphant’s The Rodin Project opened in Paris in January—this is its London one-day showing prior to its full run at Sadler’s Wells in October 2012. It will be touring nationally and internationally before London gets to see its honed version in autumn. And, beautiful masterpiece though it is, the soporific first half could do with a little honing.

Visually stunning, for which stage designers Es Devlin and Bronia Housman and lighting designer Michael Hulls must take the bulk of the praise, it is a tour de force from Maliphant with all his exquisite language of form and flow.

How to transform a solid sculptural form into kinetic plasticity, how to make it dynamic in dance? Maliphant has opted for dancers from as diverse a range of dance and movement as street, popping, breaking, free-running parkour, t’ai chi, capoiera, and contemporary dance. The body building six-pack bulk of Dickson Mbi, the lithe speed of Tommy Franzén and Thomasin Gülgeç, and the steely grace and beauty of Ella Mesma, Carys Staton and Jennifer White…

An artist’s studio draped in endless dustsheet bolts, plinths and steps the cliffs of ancient Greece. A photoshoot and a magic lantern show. Dancers pose—the three graces, men in slow motion sparring combat—sculptural classical mythological Greek tales come to life under Hulls’s silver moonlight, pink and golden sunset glow, pale watery dawn.

Sea breezes blow the long white drapes, adjusted and rearranged by the dancers. The Odyssey, the sirens on the rocks, the Lotus Eaters... we stay too long on this promontory. Alexander Zekke’s new score, cello sounds Mediterranean, Middle-Eastern, and electronic, assists the drifting mind.

The second half is urban, black rocks, constructivist blocks, and square wall that turn concrete grey in the light. Costumes (by Stevie Stewart) street joggers and shiny tops. The tempo picks up. Lotus Eaters are driven away now by sharp Latin sounds and street credibility. Bodies slip and slide, leap, somersault, cartwheel, twist and run.

A mindboggling vertical ballet on the wall… The Gates of Hell? Bas reliefs defying gravity, brothers in arms, shoulder on shoulder, Dickson Mbi and Tommy Franzén run softly gracefully up and down, gymnastic, cool and shockingly beautiful. It looks impossible, but they make it look deceptively easy.

Hulls’s lighting picks out hands and arms in flickering sculptural light. In the corner a girl, her beautiful naked body given form by the crepuscular light, looks over her shoulder. Process is what Maliphant is making us see, the sculptural process, the model on the plinth. Astonishing and magical. A masterful Maliphant brings static form to life in a transfixing son et lumière show.