Peter Brook's Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord is in a Parisian neighbourhood often referred to as the 'ghetto' or the 'no-go area'. Metro trains rattle along the ugly elevated railway, above vociferous traffic jams and pavements spilling over with multicultural crowds. The gently wafting aromas of Indian restaurants and African grocery stores can be sniffed on the breeze. Inside the building, the Bouffes' unrefurbished auditorium with pocked walls and splendid, stripped-down dome looks more like a cathedral devastated by war damage than the gilt and plush bourgeois theatre it was in the 19th century. There is something majestic about the crumbling remains of the stone proscenium and the bare walls. It has the air of an aged Hecuba after the sack of Troy, head still held high, and what it has lost in gilt and velvet, it has gained in calm, unadorned dignity. Minimalist, yet atmospheric, it is protean, blending and fading and springing to life in tune with the dramatic imagination. And it is an apposite environment for the characters of Fragments. The Irish playwright, himself an immigrant in Paris, first found shelter for his desolate but endearing vagabonds in the avant-garde 'pocket-theatres' of the post-war left-bank. Fame swept them into the mainstream, but the Bouffes, redolent of dereliction, seems like an apt refuge for Samuel Beckett's obscure and displaced characters.

Brook himself is 83 years old, a grand old man of the theatre, something of a monument in his own right. Still clear as a bell, ever enthusiastic, he can be seen in the foyer and the café on opening nights shaking hands with a welcoming smile. Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord has been his theatrical home for thirty years, the 'empty space' where he has staged works as epic as The Mahabharata, as renowned as Hamlet and Carmen, and as modest as The Costume and Beckett's short Fragments. During a career in theatre, film and opera spanning sixty years, he has worked in venues stretching from Stratford to the townships of South Africa, passing on the way through the African desert, the ruins of Persepolis, a deserted quarry and an old Glaswegian tram shed; ever experimenting, ever searching for that special theatrical 'space', in time and place, where audience and performers interact to create the event: a relationship that came naturally in the theatres of Elizabethan London and Athens in the 5th century BC.

Brook has always taken an unconventional approach to the classics. In the '60s, when he had already reached the pinnacle of his profession, he cast it all aside to experiment with the work of Antonin Artaud and Jerzy Grotowski. It was this espousal that led to the renowned liberation of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, a play which had disappeared beneath the accretions of the 19th century spectacle. After the phenomenal, but not entirely uncontroversial success of the Dream, Brook established himself in Paris and continued to experiment with his multicultural company at the International Centre for Theatre Research, reclaiming his theatre from the rubble. His strength as a director of film, opera or theatre lies in his refusal to take anything for granted.

And so it is with Fragments. Brook refuses to adhere to the conventional views of Beckett's work, nor to take Fragments at simple face value. Beckett, most famous for writing an astonishingly successful play in which, as one critic put it, 'nothing happens twice', is generally treated either with utmost reverence or satirical scorn. The plays are too often deemed profound and gloomy pronouncements on the absurdity of these puny creatures that constitute the human race. Beckett is deemed fundamentally and bleakly pessimistic in spite of a black and sometimes absurdist humour that runs through the works.

According to Brook, the usual adjectives applied to Beckett, such as desperate, pessimistic and negative, are all wrong. Beckett was courageous enough to cast an unflinching scrutiny into the abyss, without recourse to comforting dogmas or the usual consolations proffered by a materialist society. He was a relentless pursuer of the most terrible truths, and, armed with his saving sense of humour, he shared with his characters the awful uncertainty, the pain, as he watched them flounder in obscurity and the unknown.

Uncompromising is a term often used pejoratively when referring to Beckett, but Brook can turn it into a virtue. If Beckett was a perfectionist, it was in his search for these elusive truths, and in his search for a minimalist form that would most aptly express the essence of his creatures, their every breath, their rhythms, their movements, their sounds.

Like the Elizabethans and the ancient Greeks, Beckett created creatures who dared to hope, to think the unthinkable, and to face up to their ultimate destiny: the inevitability of incomprehension. Beckett espouses the characters who would ordinarily only cross the stage in supporting roles. Brook has succeeded in giving them dignity on a human scale. The performance is inclusive in the best sense of the word; we are embraced in the modesty and shared understanding of what it means to be human.

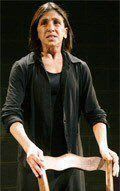

Kathyne Hunter, Jos Hoeben and Marcello Magni trained at the Ecole Jacques Lecoq in Paris before founding Theatre du Complicite with Simon McBurney. They are the crème-de-la-crème. Hunter is absolutely riveting as the solitary woman living life in permanent deferral, waiting to replace her mother in the rocking chair, acknowledging but barely daring to question the inevitability of life's course. It is worth seeing this production for her alone. One could hear the audience holding its collective breath as, dressed simply and even elegantly in black, she spoke out loud of her incomprehension, rocked back and forth, or paced the floor. Her voice has an unusual quality: rich and vibrant, it tantalises and lulls the listener and entices us into her dark and barren visions. Interiority or everyday landscapes strangely turned surreal? With Beckett the real and the metaphor merge.

Jos Hoeben and Marcello Magni are delightfully funny in an all too short piece about two opposing attitudes to daily existence in an inscrutable universe: living in white sacks, with one suit of clothes between them, and oblivious to the other's existence, one is the eternal pessimist and the other the ebullient optimist summoned to consciousness by the prodding of a pole from on high. The pole, which is just a pole on a string, has an uncanny knowledge of exactly where they are. The pair of them are equally as engaging in the first short piece as a blind musician and a one-legged man who has lost his son. As a finale, the three actors, as three old ladies, perform a short comic piece which hides a powerful sting.

This is a mature reading of Beckett which brings his more humane and mellow qualities to the fore without pulling the punches. It is modestly elegiac and yet earthy and comic. It embodies the playwright's contradictions in a nutshell. If I have any criticism at all, it is that the evening is too short and we are left wanting more.

Until 19th April

Philip Fisher reviewed this production at the Young Vic, David Chadderton at The Lowry, and Pete Wood at the Nuffield, Southampton