Opera North’s 2016 programme at The Lowry closes with a double bill of one-act operas by Puccini.

It is a general rule that rarely-produced pieces, even by great artists, are rarely produced for good reasons. Tonight is not the exception to prove that rule. Nevertheless, because this is Puccini and because this is Opera North, there will be no shortage of delights on offer.

Il Tabarro is unusual in Puccini’s work in that its cast of characters is proletarian (though, strictly speaking, I suppose we should call a barge owner petit bourgeois). It tells the tale of Giorgetta, the young wife of Michele, who owns a barge transporting goods along the Seine. The taciturn but largely decent Michele employs a small group of labourers to load and unload goods. One of these workers, Luigi, has become Giorgetta’s lover. The discovery of this infidelity will lead to the opera’s tragic finale.

Johan Engels’s set is not without its vrirtues. The repeated image of men, laden with heavy sacks, lumbering out of the gloom of the hold is powerful (if only the men could give a more telling impression of weary souls who have spent a long day "toting that barge and lifting that bail".) However, the large offset rectangle that represents the barge seems to cramp the movement of the performers, and the sight of them, balancing aloft while singing their hearts out, creates a distracting sense of jeopardy which detracts from the genuine drama of the story being told.

Ivan Inverardi’s Michele, a stern, taciturn man, still much in love with his wife, prowls impressively about the stage, like a hungry, lonely bear. I like him and his voice.

Giorgetta, as portrayed by Giselle Allen, is a down-to-earth, self-assured woman, nursing heartbreak and the need for romance. When her husband, in his own defence reminds her that he never beats her, her reply that she would prefer "bruises to silence" is telling. Allen’s singing, a perfect marriage of need and resilience, fits well to the role.

The articulate and politically passionate Luigi—who reminds me of Caveradossi and makes me wish these characters and their lives had been explored at greater length—is played by David Butt Philip. His voice admirably punches through the notoriously dead acoustic of the Lowry’s Lyric theatre (except where Jac van Steen’s conducting permits the orchestra to gain the upper hand).

Anne-Marie Owens deserves a special mention for getting right inside the skin of La Frugola: one of those working women who grubs for a living, all the while dispensing humour and pearls of demotic wisdom.

The main issue with this production lies in the finale. How to handle an unavoidably melodramatic closing scene is a difficult choice but David Poutney (or perhaps Michael Barker-Caven who directs this revival) gets it terribly wrong. The hold of the barge suddenly becomes a tableau vivant, with the killer now backlit, striking a camp pose even D W Griffith would have wanted reframing. Not good.

Suor Angelica tells the story of a woman of noble birth, forced into a nunnery for the “crime” of having an illegitimate child. Seven years on, Sister Angelica (now the convent’s expert in medicinal herbs) still yearns for news of her son. One day, her aunt, the princess, arrives. As executor of the family estate, she is here to demand Angelica signs documents renouncing her inheritance. Before signing, Angelica pleads for news of her child, only to be told that he died two years ago.

These mournful tidings tip Angelica into a brief but fatal insanity, during which she self-administers a deadly concoction. Realising, too late, that she has committed a mortal sin, she pleads with the Holy Mother to send her grace and allow her to be reunited with her child in Heaven, rather than damned as a suicide. The Virgin hears her prayer.

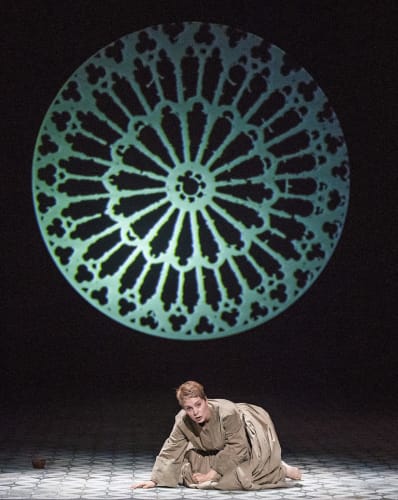

The piece is, for the most part frugally staged with a monochrome set. The sense that Puccini was writing an anti-clerical work is sustained by an enormous cross, hanging like a bird of prey over the nuns’ heads. However, all such subtleties are thrown to the wind in a finale that sees Angelica (or presumably now, her spirit) cast aside her robe and walk, naked and with arms outstretched, towards a large, circular stained-glass window. As she approaches, the window first kaleidoscopes, then melts into images of stars, then galaxies, finishing with the image of a foetus superimposed on the universe.

I hold my hand up as a grizzled, old atheist. Even so, I am not beyond being moved by the ethereal and the spiritual. This, however, comes across as a digital age version of Stephen Pearson’s phenomenally popular 1970s image, “The Wings of Love”. (My apologies, if you still have a copy on your wall).

With van Steen now having the orchestra under full control, we (gratefully) witness some excellent vocal performances.

Patricia Bardon perhaps needs better direction as the Princess—her movements are sometimes too decisive, her gestures too grandiose. Her voice, though, is marvellous, with all the merciless gravitas of a privileged woman performing an onerous but necessary duty.

Anne-Sophie Duprels is a joy as Sister Angelica. Her portrayal of Angelica’s temporary loss of sanity is fragile and moving, and her control of the final note of “Senza Mamma” the highspot of the evening. Whilst, given this finale, we can scarcely expect to see more of her, we must certainly hope to hear much more of her in future ON productions.