This was the first play of Shakespeare’s that I ever saw. I remember the King borne in on a litter doing a death roll down a flight of steps but not much else (the director was Peter Brook and Paul Scofield was playing the Bastard), but it was long ago and I was very young. I saw it a couple of years later at Stratford (with Helpmann and Quayle) but never since, for productions have been comparatively few. It is a play that was popular in the past (Sarah Siddons was much admired as Constance and the opportunity for medieval pageantry attracted the Victorians). Why is it so rarely produced today? The Union’s revival makes you wonder for Phil Willmott’s production gives it vivid life.

This is not the King you know about—there is no mention of Magna Carta or the crown jewels lost in the Wash. Indeed the crown has to be wrenched out of hands that still grip in firm in death. We are not in a world of fluttering banners and medieval pomp but grappling with the real politic of power. This makes the medieval monarchy feel like a modern world of political chicanery complete with spin doctors, duplicity and opportunist deals. It has a very contemporary resonance and must also have done for its original audiences four hundred years ago. I can’t help wondering how the Shakespeare ever got it past the Master of the Revels’s censorship.

It is all about “a sceptre snatched with an unruly hand” as the Papal Legate Pandulph puts it. After the death of Richard Coeur de Lion, John claims the crown that, by primogeniture, should have gone to Arthur, his elder brother Geffrey’s son. Arthur’s mother, supported by the French king, claims it for her son. Pandulph is initially involved because John is preventing the Pope’s nominee from taking up his post as Archbishop of Canterbury but (voicing Elizabethan Eeglish Protestantism) John lambasts the Papacy and indulgences before succumbing to the Cardinal as a ploy. A marriage between John’s niece and the French Dauphin brings temporary diplomatic accord but wars continue in which Arthur becomes John’s prisoner. The French attempt to invade England but their fleet is wrecked and, when John dies, probably poisoned by monks, his son succeeds as Henry III.

This isn’t a tragedy, it’s a squabble, though one that leaves many dead soldiers on the battlefield and sacrifices little Arthur, but Siddons obviously saw the passionate and grieving Constance as a tragic role. Samantha Lawson plays her in a way that makes you understand what her famous predecessor saw in the role but she also brings out her politcal nous, as she tries to manouvre the French, and a vicious tongue as she lays into John. It is just one example of the high octane playing that fuels Phil Willmot’s production.

Nicholas Osmond as King John gilds his deviousness and opportunism with good-looking charm. He knows how to play the shining monarch while ordering murder. Maggie Daniels as his mother, the aging Eleanor, is ruthless behind her gentle grannie façade. Damian Quinn makes French King Louis seem more honest but when this production shows him, ranged like the English before the walls of Angers, addressing its townsfolk, both kings are like politicians on the hustings or making television speeches, complete with patriotic music welling up to heighten the effect, each as calculating as the other. There is black humour here, satire if the politician-speak didn’t seem so horribly accurate, a moment of wickedly-raised royal eyebrow invites complicity from the audience. More humour comes in the presentatio of Pandulph: a joke at Rome’s expense that Michael J Hayes clearly relishes but is careful not to overplay. Against these others the Dauphin (James Corscadden) and his bride Blanche (Daisy May), and of course young Arthur (Albert de Jongh), are contrasted youthful innocence.

While the great ones fight over a kingdom, two lesser men, the supposed sons of Sir Robert Faulconbridge, fight over an inheritance. The younger brother claims it, saying the elder is a bastard. When it turns out the putative father was Coer de Lion, the royal family welcomes him as their own and bastard Philip decides that’s better than his father’s land. He becomes part of the royal team, spin doctor almost, always pitching for the King until disillusion makes him question things.

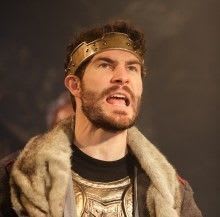

Young Robert is as full of self-interest as all those higher in the world, but his long-haired, relaxed manner contrasts with the manic spontaneity with which Rikki Lawton plays the bastard Philip who seems, like a spin-doctor, always around. Indeed he seems so much in charge behind the scenes as ‘twere that he is often moving them, but always it seems naturally integrated in the action. This is a performance of enormous vitality, connecting with the audience like a frantic stand-up, full of pace and emphasis and obviously carefully thought out but his fragmented delivery plays havoc with the sense which arrives more by osmosis than by hearing. When, for no apparent reason, an emphasis comes out on “a” or “the”, can the character really be thinking this? At its most extreme, “warlike John” comes out at one point as “war, like John”. That’s not what was meant by “trippingly on the tongue” and it is something this charismatic young actor must watch. It is especially noticeable because this cast generally handles the verse well.

Willmott’s production delivers the play in about two hours plus one interval. The speed is aided by judicious cutting and rapid transitions from scene to scene. Sequence seems sometimes to have been rearranged so that they intersect with each other. One action continues in the background while another takes place. Emma Tomkin’s design uses a black wall on which an heraldic emblem has been chalked and a row of black tables which can be rearranged to suggest locations or separate opposing forces. Light heraldic breastplates that could have come from some chivalric toy department are worn under military great coats that could have been Napoleonic uniform, seen in the trenches at the Somme or on the backs of a modern army. The niceties of rank and presidence however are ignored, emphasising the personal confrontations and increasing our engagement.

The production is full of items of business that add to our understanding and visual touches that heighten effect. In one physical addition John Last’s excellent Hubert, the king’s servant who is ordered to kill Arthur, is seen heaving and dragging in corpses prompting the king to make him the murderer. Slightly adjusting one speech and bringing it forward, Willmott creates a scene that enacts what Arthur otherwise describes, showing the bond between him and Hubert and this scene continues in the background as Arthur’s mother, with the French, bewails his loss. Huibert is the one character who really changes and comes out well, the dutiful royal servant becomes a compassionate man prepared to stand up for right.

In what is probably the best known scene in the play, a blow torch substitutes for the red hot irons with which Hubert proposes to put out Arthur’s eyes. This touch of modernity did not entirely convince me of its practicality. It saved exposure to some less realistic prop but it made it difficult to create that terrible last moment before Hubert relents, though these things are subjective and their gasps showed it shockingly effective for many in the audience.

This production breathes new life into the play and makes it for today. It is a small theatre. Get a ticket while you can.