Hard on the heels of Ivan Putrov’s Men in Motion comes Sergei Danilian’s Kings of the Dance. But is there such a paucity of choreography for men—Leonid Jacobson’s Vestris, Morel et Saint-Loup from Roland Petit’s 1974 Proust, and Nacho Duato’s Remanso figure in both.

Leonid Sarafanov, Marcelo Gomes, Denis Matvienko, Roberto Bolle and Ivan Vasiliev, the present reigning kings, a solidarity of brothers in art, are superb, no doubt about that, but who choses the kings’ vehicles? How is the programming decided?

Not that that sort of thing matters to audiences, give them panache, party tricks, and testosterone, and a standing ovation is guaranteed. Though there were grumbles about the two thirty-five intervals, the first one after Duato’s twelve-minute Remanso, the second after Roland Petit’s sixteen-minute Le Jeune Homme et la Mort.

Duato’s opening Kyliánesque aperitif set to music by Enrique Granados is elegant, lyrical, and showcases the dancers’ beautiful line and grace. Sarafanov, Matvienko and Gomes play hide and seek over the garden wall and dance a Rose Adagio, the rose tucked behind knee and between teeth. The backdrop, an Ellsworth Kelly square, lit in seasonal colour washes, shows off the male form in high relief against it.

The evening ends with a selection of petit fours—five titbits, again showing off male form, if not much character, epitomised by the first of the five: concept and choreography by Massimiliano Volpini, Prototype is a Wayne McGregorish computer-generated analysis of ballet’s form, a geometric exposition of ballet moves, alignment, and the body beautiful.

Danseur noble Roberto Bolle in effect dances with screen clones of himself in extracts from Giselle, Romeo and Juliet, William Forsythe’s In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated, until the ripples and stars of the galaxies take over.

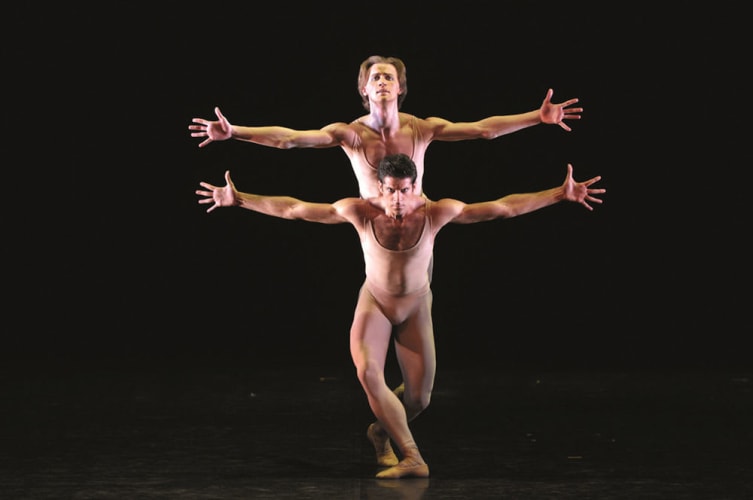

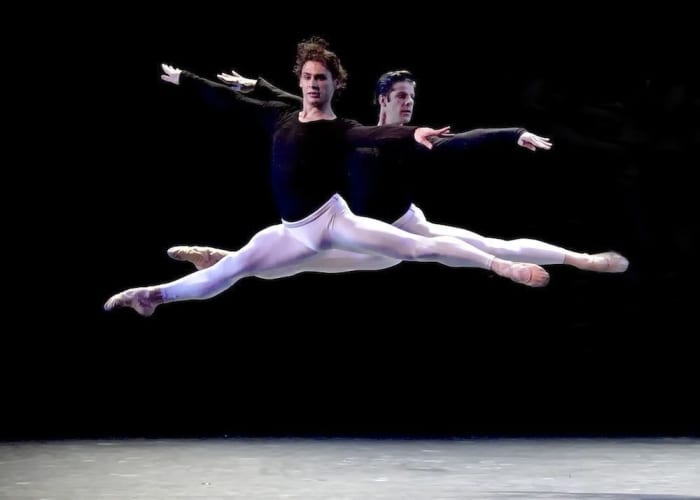

In flesh-coloured unitards, Matvienko and Gomes are the intense confrontational mirror pair of lovers in Roland Petit’s Morel et Saint-Loup (music by Gabriel Fauré), the lovely Sarafanov is miscast in Vestris, but Vasiliev in a dialogue with Tomaso Antonio Vitali’s Ciaconne in G Minor for Violin and Piano pulls off the most amazing grands jetés at remarkable speed in Patrick De Bana’s Labyrinth of Solitude, circling the stage like a thoroughbred circus horse, cantering light-footed and loose until he breaks out in explosive elevation and twisting turns, which have the audience on its feet.

A knock-out performance before the finale KO’d, choreographed by dancer Marcelo Gomes to ballet dancer turned composer Guillaume Côté’s Piano Sonata no. 4 in F# minor, in which all five are allowed to shine alone and together, tugging, playful puppies, Vasiliev the most exuberant of them all.

Different body types, different horses for courses, all excellent needless to say, but it is Vasiliev’s night. After the sizzling main course dish, Le Jeune Homme et la Mort, in which he blew everyone away, there is no stopping him.

I’d have been happy to have his performance in Le Jeune Homme et la Mort on a loop all evening. His flying horizontally through the air may be startling, but his intensity of performance is the thing. Compact like Baryshnikov and Jean Babilée on whom it was made, his petite mort duel with dominatrix death is breathtaking.

Corkscrew turns, earth-defying gymnastic spins and scissor jumps, chairs kicked over, table overturned, plunges and lunges, fighting against time, against the inevitable in aroused dance, in impassioned conversation with death and Bach’s powerful Passacaglia in C Minor, BWV 582, Vasiliev is a Pierrot, a Petrushka in destiny’s cold embrace.

Svetlana Lunkina’s seductive controlling femme fatale, who blows smoke in his face, and prepares his noose with dispassionate glare, plays this lonely poet in his garret like the Hamlet instrument he is. And leads his soul (Cocteau’s libretto a variation on a theme—see his 1950 film Orphée) into the underworld over the rooftops of Paris.

Note that Bolle is alternating with Vasiliev in Petit’s 1946 one-act existentialist ballet: Vasiliev 19 and 21 March, Bolle 20 and 22 March. The set comes courtesy of the English National Ballet, and it is the setting up and taking down of it that probably necessitates the long intervals. Well worth the wait, Le Jeune Homme et la Mort is the highlight of the evening. I’m still feeding off the memory of it.

A happy band of brothers takes the curtain call, young men at the top of their game, riding the crest of the male wave, hitting the heights—looks fun.