The title of George Dillons latest one-man performance sets out its wares but also begs the big question. As any Oxfordian will tell you, while the hero of the piece, Edward de Vere 17th Earl of Oxford, may quite feasibly have provided the prototype for some aspects of Hamlet, he is also front-runner to have actually written the plays of Shakespeare (always assuming, that is, that youre not one of those Stratfordians who persist in believing they were penned by the comparatively obscure figure of William Shakespeare. There is also a Baconian party, but the feasibility of their candidate would seem to be on the wane in recent debates.)

Dillon didnt quite lead us down that path, though it was left seductively open to view. It wasnt really necessary to engage with such controversial issues when the raw historical material is already so richly-laden with politics, romance, treachery, adventure and the unassailable ego which was obviously the birthright of the aristocratic Elizabethan male. It says a vast amount for Dillons performance that it engaged his audience in such a satisfying way with a character who was pretty despicable in modern terms (though the excuse that he couldnt attend his first wifes funeral because he was off fighting the Spanish Armada does have the ring of period authenticity to it.)

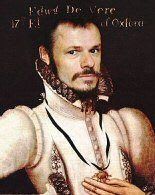

Its easy to see why Dillons performances have made him the toast of the Edinburgh Festival. This was pared-down, intimate theatre demanding sheer bravery on the part of the actor, who takes the stage armed with nothing more than a skull, a rapier and an elaborate set of lighting cues. A neat beard and a big shirt will do wonders to focus our attention, however, for with such minimal accoutrements he convincingly presented himself as a man whose expectations were as unquestioningly Elizabethan as his manner was direct and absorbing.

The journey through Oxfords life isnt an easy one to boil down into a soliloquy, so the evening was a virtuoso display of dramatic range that never risked coming close to over-statement or caricature unlike his subject, Dillon is a master of subtle, unspoken control. Oxford was twelve when his father died and his mother remarried with unseemly haste, so the story starts with an arrogant, bewildered boy, aware that he is being shunted out of his family, but never relinquishing a jot of his aristocratic status and identity. A royal ward educated in the house of Sir William Cecil (whose daughter he married with less than harmonious results), he became a curious mixture of Renaissance Man and upper-class lout, and it was fascinating to see gradually revealed an individual who could encapsulate all the gentlemanly arts while nonetheless cherishing a concept of honour that sounds dangerously close to piracy.

Later in life (he died at 54), having travelled all the recognised routes to glory and self-fulfilment and found them disappointing, Oxford found solace and involvement (not to mention royal approval) with the acting companies to which he stood patron. But did he also find time to write the plays that survive under Shakespeares name? It was cunningly left to the words and circumstances of the piece to suggest this argument without polemic. Cecils advice to the aspiring young man was a brilliant example of this technique, with the sentiments of Polonius homily to Laertes recast into an entertainingly uncanonical, yet recognisable, variant. One Will Shakespeare is, however, mentioned - as an egg-headed boy of no book-learning who eventually finds his way into Oxfords household en route from a shrewish wife for whom he cannot write poetry.

The enthusiastic response to this game did defuse the one issue I might have taken with the piece how well are you expected to know your Shakespeare in order to appreciate it? The audience at South Shields may have been small (the production might have been put on to better effect in a studio space rather than an under-filled formal theatre) but it was clearly appreciative, and though many of the textual references were obviously being picked up, I suspect that essentially it was the performance itself which impressed. Afterwards I heard someone describing the courage of Dillons acting, and certainly in theatre of this direct and unadorned kind, there isnt a safety-net. The clarity of delivery, assurance of movement and generosity of spirit which characterised the whole project were so rewarding that I feel like an absolute churl when I say that Im still rooting for Will from Stratford as the onlie begetter of those everlasting plays.