Svetlana Zakharova—the Bolshoi’s prima ballerina and the first and only Russian étoile at Teatro alla Scala—in two UK premières, a double bill that showcases the elegant, leggy ballerinas of the Bolshoi and the strength of its male dancers, what could go wrong? The dancers are truly magnificent.

Visuals, costume and set designs are excellent, as is the atmospheric lighting, but the lack of live music does composers and dancers a significant disservice. And the choreography rambles.

Certainly it meanders in the first forty-five-minute plotless, academic and abstract, hyperventilating piece, Come un Respiro (like a breath), by former dancer Mauro Bigonzetti. Responding to Handel’s baroque piano music (sounding horribly distorted on the Coliseum speakers), there’s nothing serene about it.

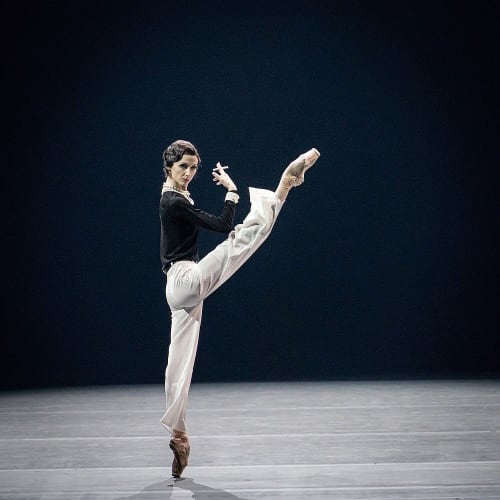

Sixteen dancers buckle and bend in rippling rope formation, speed through duets and solos (Zakharova in a razor-sharp ‘Black Swan’ solo, legs like fencing foils) and fight with the music. Arms semaphore—what are these playful marionettes trying to tell us with their cryptic angular hand jive?

Costumed by Helena de Medeiros in mock baroque tight bodices and tiny bustles of feather and slinky concertina coils, wittily hinting at the music’s period—makes me think of Mozart’s naughtiness and commedia dell’arte buffoonery rather than Handel—dancers scribble and tie themselves in knots and origami folds, do ungainly splits, hip swings and supremely high extensions. I think Paul Klee and Joan Miró.

The three Bolshoi male principals Denis Savin, Mikhail Lobukhin and Vyacheslav Lopatin perform feats of athleticism worthy of the Olympics, but new to me is Jacopo Tissi, leading soloist at the Bolshoi, formerly of La Scala Ballet, a beautiful dancer with lovely arms, one to watch. He’s the only one who looks as if he is enjoying himself. The Gaynutdinov twins make me think of Tweedledum and Tweedledee (or should that be Nijinsky and Nureyev?)—I am not being irreverent, as I think postmodern irony and irreverence are built into the work.

Amongst the girls, Ana Turazashvili is outstanding, but is the ugly crotch to the fore and bums in the air geometry meant to be erotic? These challenging acrobatic gymnastics and twister contortions look awkward to me. Less could be more. But what instruments these bodies are, Zakharova’s the most refined, what can't she do…

The second, hour-long, piece, Gabrielle Chanel (premièred at the Bolshoi in June this year), of the double bill is meant to be the pièce de rèsistance. It’s a biography in dance of Coco Chanel after all. Her rise from poverty though music hall to legendary couturier and perfumer, her love affairs and her links with Diaghilev and Les Ballets Russes. Her essence… Her besoin d'être aimé. Her interior life which Zakharova tries to embody in long solos. Her shrewdness: style never goes out of fashion.

On video, we visit her flat, go to the races, see film of fin de siècle fashion before she liberated it, taking away its layers, hats and raising the hems. Film overlaps with dance, a springboard for the storyline. A reed-slender Zakharova is Chanel; the men in her life are rich lover Étienne Balsan (Lobukhin), dancer Serge Lifar (Lopatin), the Perfumer (Savin) with whom she created her signature perfume and her handsome ill-fated lover ‘Boy’ Capel (Tissi) who really must be the one if her swinging pendulum legs mean anything.

Dancers in her Riviera bathing costumes recreate Le Train Bleu (1924) and Lopatin is Balanchine’s Apollon (1929) with his three muses (Turazashvili, Svetlana Pavlova, Victoria Litvinova). What could be more suitable for balletic treatment? Again, the dancing can’t be faulted but, fascinating though it is, it’s a patchy hour with too much busyness.

Music is by Ilya Demutsky, who worked with San Francisco Ballet choreographer-in-residence Yuri Possokhov on his A Hero of Our Time and the controversial Nureyev for the Bolshoi Ballet. It’s a heady mix, but it’s hard to judge the over-amplified recorded music, cinematic, dramatic, hectic, deafening at times and quite frankly a screeching killjoy distraction from the stylish scenes on stage.

A black constructivist paneled set by Maria Tregubova—with video design and projections by Ilya Starilov and enhancing lighting by Ivan Vinogradov—backgrounds black and white Chanel designs (apparently more than eighty costumes have been designed exclusively for the ballet by CHANEL Creative Studio) and Chanel’s maxims in white cursive script—in French, of course (there are surtitles).

Wonderful to see Bolshoi dancers and their superlative technique, so one mustn’t grumble. It obviously was a pleasure for Zakharova to research Chanel and visit her apartment with its Russian influences, but how come one feels so disengaged? It’s a monochrome evening.