Quentin Crisp is one of the very few people who can be unequivocally described as unique.

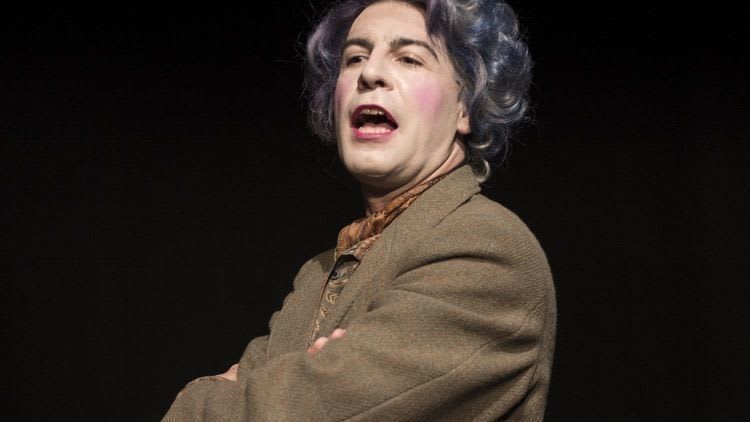

In Mark Farrelly's solo show celebrating Crisp's life, we first find him, as flamboyant as an impoverished, gay "one man Oxfam" can be, in his modest and filthy Chelsea home of 20 years.

Despite approaching his sixties, these are still his pre-icon days. The 1975 film of Crisp's autobiography, The Naked Civil Servant staring the BAFTA-winning John Hurt, had yet to propel him into the global limelight.

Farrelly's 1960s Crisp is reflective. Lonely, and unsuccessful in the world of work until he found employment as a life model—something he could be rather than something he could do—his effeminate, colourful exterior and determined unwillingness to moderate his lifestyle to suit others made him an outsider.

Farrelly's always witty text tenderly captures the loneliness of being "a minority within a minority" but neither that nor the loss of a quickly spent love affair are dwelt on or embellished with self pity.

Crisp had been an openly gay man from his twenties and life of hard knocks doesn’t even start to describe the indignities he suffered. Gay bashed, barred from cafés and clubs, rejected for service during WWII for sexual deviance and arrested for importuning, Crisp paid dearly for his courageous protest.

No wonder he developed a string of philosophies expressed in comically barbed terms to get through a lifelong unwillingness to compromise.

The success of The Naked Civil Servant changed Crisp's life irrevocably. Within a few years of the film's release, he was on stage in London's West End, a feted raconteur and wit.

His fame and notoriety took him to New York where he once again lived in a one-room apartment, which he found "painted the colour of despair".

In the US, he alienated the local gay community, as he had done at home, with his unwillingness to align himself to their cause. Always believing that homosexuality was an illness, Gay Pride, he said, was an oxymoron.

Also, as he had done at home, resolutely true to himself, Crisp found success and affirmation on stage.

Vocally, Farrelly captures Crisp's long vowels and physically his natural propensity to take up a pose. His intelligent and sensitive portrayal of Quentin Crisp, growing old before our eyes, is a joy to witness.

The underlying sadness of the 1960s Crisp remains apparent in the later scene which finds him on stage in New York, but he is illuminated by the delight of having an adoring audience hanging on his every scathingly funny word.

Laugh out loud funny, Quentin Crisp: Naked Hope also reveals the dual tragedies of Crisp's 90 years, his self-proclaimed immunity to love and the late arrival in his life of acceptance and approval.

That he achieved the latter after a life without concession is a testament to his self-belief and the timelessness of his call to "discover who you are. And be it. Like mad!"

After playing The Jack Studio Theatre the tour of Quentin Crisp: Naked Hope visits Stamford Arts Centre, Live at Zédel London, Millgate Arts Centre Saddleworth and Merlin Theatre Sheffield. The show supports anti LBTG+ violence charity GALOP.