The final triple bill, and what have San Francisco Ballet Company dancers left to prove? That they can get the better of whatever choreographers throw at them—they bring dash and flair to Christopher Wheeldon and David Dawson's screensaver ballets, and character and natural energy to Trey McIntyre’s slice of Walt Whitman Americana.

It’s the middle piece, McIntyre’s Your Flesh Shall Be a Great Poem, quirky, joyous, stirring, which is the most memorable of the three. A lengthy title taken from Whitman’s 1855 preface (it’s worth reading in full) to his Leaves of Grass poetry collection, it pays respect to McIntyre’s grandfather, an undertaker no less.

A newly found 1920s photo of grandpa, an eclipse of the sun on the first day of rehearsals, and McIntyre had his way into the past—a ‘portal through time’ of the eclipse, he says. His grandpa’s dementia plays a role, too, in the evocative vignettes of his life, Chris Garneau’s folksy songs the perfect setting, an eclipse projection on the backcloth.

Benjamin Freemantle’s soft avian arms solo sets the tone: here is a young man flying towards the light. Male friends join him—jocks in costumes suggestive to me of The Great Gatsby. Male friendships à la Whitman, heads on shoulders, till a man is left alone to be joined by a young woman.

Then by two frisky, leggy girls in baby-doll nighties—and do Sasha De Sol and Jennifer Stahl have fun with them. Do I hear a Kurt Weill cabaret rhythm? Sharp legs, soft arms, they bewitch me never mind the men.

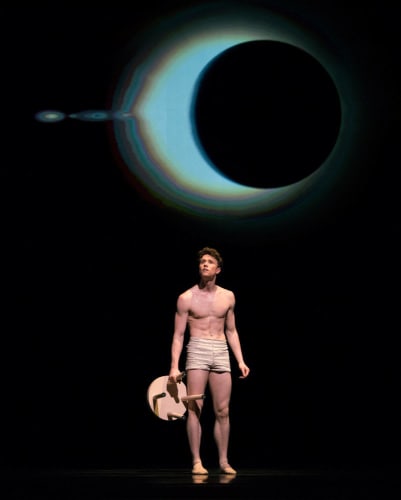

The piano makes me think of silent movies, and there’s a happy country gal and her beau that could have stepped out of any Hollywood musical of the period. But then, there’s a cloudy night sky video projection (grandpa’s clouding mind?) and Freemantle returns in boxer shorts, trousers in one hand and wooden milking stool in the other.

And dances with that stool to a fairground sound—what doesn't he do with the stool: swims on it, flies on it, handstands on it, he loves it dearly, and finally obliterates his face with it. His face a ‘Magritte’ blank—oblivion, dementia. Mikhail Baryshnikov in his Twyla Tharp and Robert Wilson phase couldn't do it better.

Christopher Wheeldon’s fondness for Keaton Henson’s introspective bedsitter compositions makes a bleak thing of our technology obsessed and possessed world in Bound To (as in bound to our mobile phones). It is only in the final section that he concedes it has its uses, a comfort in time of grief. Or is this loss of friendship?

Flickering computer screens, code scrolling like falling rain (design Jean-Marc Puissant and Alexander V Nichols), desert sands rippling, twitching individuals, faces lit by mobile phone lights, gather on the stage. Wayne McGregor, David Dawson, Liam Scarlett, and the BalletBoyz flicker before my face.

If we put them away life could be bucolic, idyllic. Nymphs and shepherds, we could be prancing in meadows green… As it is, dressed in black we turn our backs on each other. Relationships suffer: a boy shrugs a girl repeatedly off his back. They connect briefly when she removes his phone, but he gets it back and walks off.

There are eight chapters signaling Wheeldon’s thinking—Remember When We Used To Talk, Remember When We Used To Play—you get the idea—but the sermonising concept leaves me indifferent. It’s the dancers, neatly unpicking the knotted choreography, that keep my attention. Yuan Yuan Tan (in midnight blue slip) in duet with Carlo Di Lanno (Take a Deep Breath) is breathtaking. Wheeldon makes huge demands on their gymnast’s bodies, on their elasticity, balance and stamina.

David Dawson demands more of the same in his first work for the company, Anima Animus, “ballet technique stretched to its outer limit”. And the animated dancers deliver in spades, but they are set on repeat, busy buzzing bees, skittering bugs.

A monochrome scenario, a contemplative Philip Glass-ish score, Ezio Bosso’s Violin Concerto Esoconcerto (violinist Cordula Merks), Anima Animus is an endurance feat, an ultra-marathon. Wona Park and Sofiane Sylve never cease, and the others are not far behind in wafts of movement, sycamore seeds blowing in the fierce wind, the girls bendy with high extensions, the men sturdy, holding the women high as if on pedestals.

The most reflective of the four programmes, the range complete, something for everyone, these dancers can do anything. It’s been an exhausting season, but was it worth it!