If you want to see the human body revealed in all its supple sensual splendour under delineating chiaroscuro light (Michael Hulls with animation by Jan Urbanowski) Russell Maliphant’s creations are for you.

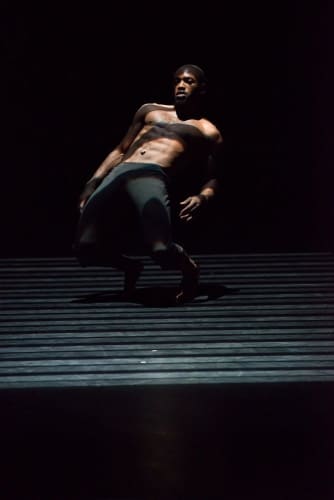

Light plays and ripples on a still, glistening torso, on magnificent muscles, as Dickson Mbi takes his place on a striped patch of light. The body crumples, twists and turns. Drums beat.

Arms spread wide in aerial flight, body low on the ground, the tempo rises. Armand Amar’s music reverberates from the ground up. I can feel it in my body. It is all about the body. Every limb, joint and sinew wants to move, muscle memory activated.

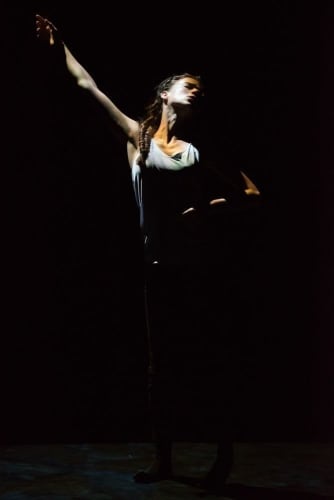

Carys Staton in white shift enters from the peripheral darkness and the dynamic shifts. Arms carve spirals and curves in ritual circling play, and the lights go out.

A man behind me shouts yes. Yes, it is cathartic, a Greek drama in its visceral visual and aural intensity. It is called Still. Who or what was dancing, light, shadows, flesh, the spirit?

Sound, light and movement an organic whole, the need to move to the beat of a strong heart is as urgent as life itself, the urge to dance is imbedded in our cells, but what about the mind's eye, the unsettling tricks of the light?

Traces follows: Thomasin Gülgeç makes his marks on the ground with his stick, implement and weapon, an extension of his arm. Russell Maliphant stakes his ground and Dickson Mbi joins him—two in red tops against the one in green, boys’ warrior play?

Cartwheels and slick stick martial art moves to Andy Cowton’s complex layers of sound are followed by more Andy Cowton in Two, a piece originally created for Dana Fouras (Maliphant’s wife), and subsequently performed, amongst others, by Sylvie Guillem, and Fang-Yi Sheu and Yuan Yuan Tan.

Carys Staton is bewitching in the solo. Maliphant talks about feeling good when dancing, about dancers bringing their own personalities to the choreography, about how it changes with each new performer. This is true, but he and lighting designer Michael Hulls sculpt the body beautiful.

Captured and centred on a shadowy small square of dramatic light everything happens in minimalist movement and time. Dying Swan arms, double-jointed shoulders, t’ai chi calmness and control, feet precisely placed, all weave a magical spell.

After the interval comes another familiar piece, Afterlight (Part One), danced originally by Daniel Proietto and reprised by Thomasin Gülgeç, different bodies, different musicality. Erik Satie’s moody meditative Gnossiennes suggest the seasons and eastern mysticism.

Memory tells me Proietto was delicate and mercurial, whereas Gülgeç brings a more masculine solidity to this chameleon creature, one minute a faun, the next a spinning dervish.

Remember twirling in giddy semi-consciousness as a child—that, too. At one with the earth spinning on its axis—light and sound melding—lost in a world of one’s own.

Still Current, the final piece, is new—a play on words that encapsulates Maliphant, his stillness and his currency. It’s the quiet ones one has to watch. And he’s also still dancing at fifty-two—impossible to believe when one sees him in his own choreography, here in duet with Carys Staton.

A duet that combines stillness and electric tensions, the current that runs through all his pieces: balance and weight, contact, soft and hard, harmony and dissension. A definition of martial arts… A flow of energy.

Heartbeats thud again (composed by Mukul), signals from one to the other, Morse code, a private world. A narrative of sorts, that maybe goes on too long—lots of repeats—but then life is like that.

Poses that remind me of Edo prints and slow Japanese films. And one particular lift on to the back from the floor then a slide down on to his lap will stay in my mind’s eye for some time.

Lights go on and off—electricity again—an ominous turn of events or an attempt to catch the moment? The light patch splits in two, harsher sounds overlay gentle oriental strings—erotic and tender love gives way to loss, separation and finality.

Maliphant, Royal Ballet School trained, has studied anatomy, physiology and biomechanics as well as capoeira, t’ai chi, yoga, contact improvisation, and needless to say they inform his choreography. But it is his work with Olivier-award-winning Michael Hulls, the integration of light and movement (and sound) that is his defining legacy.

His company is compact, but what dancers: Carys Staton is a revelation, lithe, elegant and strong—a Guillem in the making; Dickson Mbi coming to contemporary dance from popping and boogaloo is a powerful presence, and Thomasin Gülgeç who has studied Shotokan karate and judo as well as dance, is gymnastic, athletic, and strong. All three performed in Maliphant's Rodin Project.