Stavros Lillitos’s play leaps over nine years of Greek history seen through the conflicts within one family, the Scapanes.

It begins on the day in 1936 when General Mataxas declared martial law and established his dictatorship, jumps to the German occupation and then to the end of the Second World War when the British-supported right set out to suppress left-wing opposition.

It doesn’t set out to explain Greek history (when it was written in the 1950s, perhaps it did not need to) nor does it offer any political argument but tends to present revolutionary young people as the good people against an oppressive authority, idealists in a struggle against evil who are presented as heroes, whether trade-unionists or partisans.

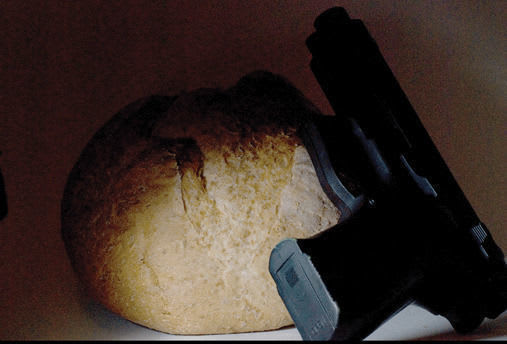

George Eugeniou’s production opens with a tableau that represents Greek tradition, or one side of it: the Scapanes family lined up either side of an Orthodox priest who is blessing the bread as they chant the Lord’s Prayer. Meanwhile to one side, two armed young men use chairs as a barricade as pistol shots ring out. That is another side of Greek tradition: the patriotic palikari with the slogan “Freedom or Death”.

The Scapanes seem to be a comfortably-off family, priest Father Savvides a welcome visitor. Though his father hoped son Alec would become a priest, he has followed a different path. An active trade unionist, secretary of his branch, he and his friend Michael are getting ready for a big demonstration (Metaxas declared martial law on the eve of a planned major strike).

There is family friction when Nestor and Helen Scapanes are entertaining the priest, a right-wing neighbour and policeman cousin Tasos and Alec comes home full of leftist fervour. Brother Yannis and sister Anna aren’t so politicised but the younger generation want to think freely. When Metaxas starts to round up leftists, Yannis convinces Alec he should flee to Salonika, telling their father he has been promoted to a job there, but before he can escape Tasos turns up to arrest him.

The action jumps now to the privations of the German occupation. Attitudes are changing. Nestor refuses to work with the Germans, Yannis is now a labourer in the docks while Tasos, a natural Nazi, serves the occupier and, as Father Nicholas explains later, the Church accepts the rule of whoever is in power (especially when they are anti-communist, of course).

What will happen when Michael, now with the resistance, turns up seeking shelter and bringing news that Alec is alive? And what will happen when the Germans have retreated and right-wing forces seek to remove all opposition?

Lillito presents his history, with its inevitable tragic ending, simplistically in black and white and Eugeniou’s direction seems to relish these extremes, deliberate stylisation sitting next to gentle naturalism.

This is more like a boys' adventure yarn than serious history. For those who don’t know modern Greek history, there is little to explain the background and they may be surprised that there is no victorious happy ending.

It is played by an international cast of varied accents and ability. Christofer Alcala brings good looks and boundless energy to his playing of Alec. Too often these days, young actors used mainly to television are mumblingly inaudible. Not he! you can probably hear him in Kings Cross, but an ultra-rapid and accented delivery take some getting used to.

Andreas Toumasis as Michael has similar energy and engagement but knows better how to control it, while Marco Aponte’s more relaxed Yiannis is gently natural once his character is established.

Tasos is a cypher villain, but Federico Moro avoids making him overly melodramatic, though that might have matched the concept. Some of the other performances are less convincing, though Vasoula Christodoulou’s Helen Scapanes and Sophia Eleni’s Anna become more real as the play progresses and Teresa Cendon Garcia lets rip as a chair-wielding crazy auntie.

The Greek political scene is still one of extremes and that is reflected in The Challenging Tide, but is this revival as timely as Theatro Technis clearly thinks it? Are there not better plays about this same history? We’ve had little chance in Britain to see work from dramatists such as Iakonos Kambanellis and Loula Anagnostaki and are there not Greek dramatists today responding to the current situation?