A fusion (I nearly said confusion) of East and West, opera and ballet, fantasy, Fantasia and fairy tale, National Ballet of China’s mythological, transcendentally ghostly The Peony Pavilion is beautiful to look at if not always easy to follow. Unless one understands Chinese: there is a female opera singer narrator, but no surtitles.

One can watch the two-hour (with interval) production without notes or background information and come out refreshed and becalmed by its dazzling stage pictures, Emi Wada’s fashion-plate costume designs, Michael Simon’s spare stage and colourwash lighting (with Han Jiang) designs, by its exquisitely unhurried pace, its hybrid musical score, which reminds me of big screen Hollywood movies with their escapist dream sequences.

Girl dreams of boy, boy dreams of girl but doesn't recognise her when they meet—is this a figment of fevered imagination? She pines away, ends up in the underworld, but is allowed to go back (or is this another dimension where the two worlds meet?), and all ends happily ever after in a grand wedding. That’s what I saw, but there’s more to it than that.

The Peony Pavilion is based on Tang Xianzu’s love-story epic written in the sixteenth century, and in its first incarnation it was a Kunqu opera over 20 hours (yes, twenty), 55 scenes, in length. A story that must have built up molecular cell by cell, and one gets the sense of that in this composite ballet version (two acts, six scenes) by young choreographer Fei Bo and director and adapter Li Liuyi.

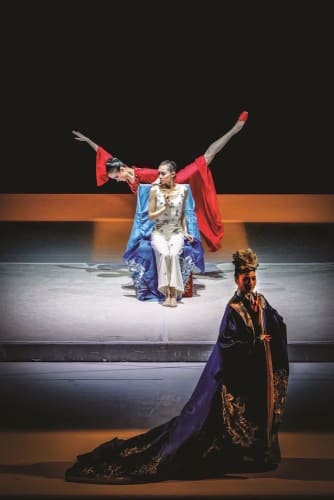

Sitting in the garden, in the magical peony pavilion, a wealthy young girl, Du Liniang, dressed in white, slips into a subconscious world, her persona splitting into three: her sexually awakening virginal self, the red clad passionate Flower Goddess of desire (Zhang Jian), and guest opera actress (Jia Pengfei), in gown of blue and gold mirroring Liniang’s cast-off own, making high-pitched verbal sense of it, gliding as if on castors, framing the tragi-comic tale. Id, ego, and super-ego?

Flower Fairies—I count twenty-four—dance, lyrical arms swaying in the breeze, as she stirs in her sleep, fantasising about the young scholar Liu Mengmei. Zhu Yan and Ma Xiaodong make a handsome couple, he fixated on her feet, she submissive and pliant with longing (Romeo and Juliet).

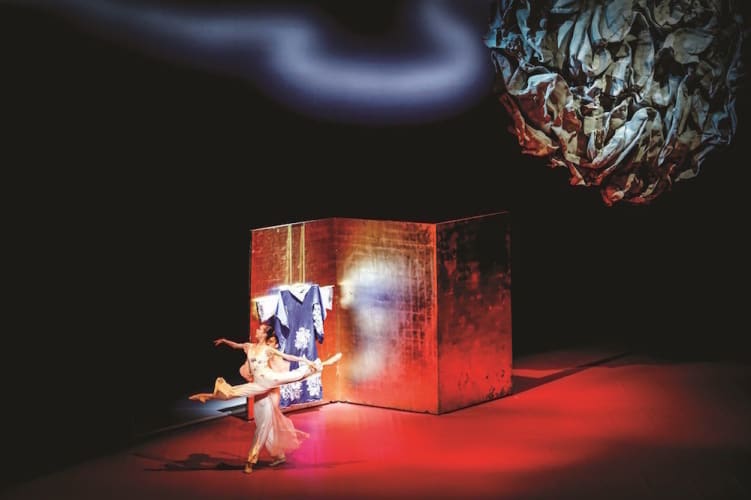

Their passionate pas deux have some extraordinary lifts, and her dancing with one pointe shoe on one shoe off is a clever mix of classical and contemporary as well as not so subtle metaphorical sexual signalling—lots of single red shoes in the corps de ballet...

He seeks her high and low—even amongst autumn-colour-clad peasants with their bundles of wood: a comic interlude to lower the temperature? She wastes away and Ghosts of Black and White Impermanence (Wang Jiyu and Wu Sicong) come to take her away. Her platform pavilion tilts, she sees herself in its underside’s distorting mirror.

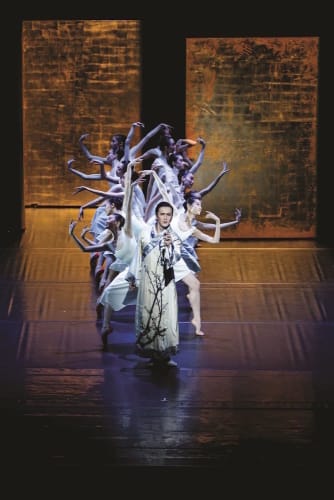

Snowflakes fall. The single branch dissecting the back changes to a symbolic one-stroke calligraphic flowing river. Act two has our hero search for her in the black snow—led by the Flower Fairies. (Cinderella, Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, Giselle, Orpheus?) Hades, the black kingdom, is ruled by the red-bearded Infernal Judge (Li Ke) and his horned demons: one in particular reminds me of King Lear’s Fool.

Sinners are judged and given punishments to fit their crimes (Mikado?) in an amusing scene, but Liniang’s story moves them all, and she is released back to the mortal world to realise her dream in a grand apotheotic ceremony and magnificent clothes of red and gold. The two yearning lovers are united and all attend their wedding, mortals, gods and ghosts. A cascade of red petals covers the empty stage – was all this a mirage or did it really happen?

Composer and arranger Guo Wenjing mixes and melds Debussy, Ravel, Holst, and Prokofiev with Chinese music, bird song, tolling bells, lush strings, and held silences. As the mind wanders seeking attachment to the familiar it lands on Shakespeare, Ariosto, Greek myths, Pina Bausch and Ballet Russes—Diaghilev would have loved The Peony Pavilion.

It opened in Beijing in 2008, was much admired at the Edinburgh Festival in 2011, and most recently played at The Lowry (co-produced by The Movement, a new producing partnership between Sadler’s Wells, Birmingham Hippodrome and The Lowry).

Refined, graceful, aesthetically pleasing and charmingly diverting in turn, The Peony Pavilion is a feather in the National Ballet of China’s (formed only in 1959) cap. Could they please bring The Red Detachment of Women or The White-Haired Girl from their back catalogue next time? I’m curious to see them live—YouTube has full-length films of both.