This is a retelling of the King Lear story transposed to an Aboriginal community in Australia’s Northern Territory in which the cast use their own words in a mixture of English and indigenous languages incorporating some of Shakespeare’s text.

It is a compacted version—95 minutes with no interval—that broadly follows the same plot with simplifications and adaptations to fit its relocation.

When actor Tom E Lewis (who plays Lear) first met director Michael Kantor, he described what was happening in his home community, arguments over land, greed for mining royalties, families divided by jealousy, as “a tragedy, just like that King Lear of yours.” Out of that grew an aim to “tell a white man’s dreamtime story… but to use it to question and probe contemporary indigenous experience.”

It is played out on a stage covered in red earth that sometimes rises in dust clouds. Over it rolls a huge metal structure, its dazzling headlights suggesting some huge lorry. It could be a mighty earthmover or a mine building. It turns to offer an interior: a house, a hovel or a prison.

Above, on a huge screen, video extends the structure or offers dark atmospheric images. (Since there is action within them and they change when there is no change of location, these can be a distraction.) There’s an on-stage band too, though Paul Jackson’s lighting ensures they don’t intrude on the scene and songs, both traditional and pop, punctuate the play’s progress.

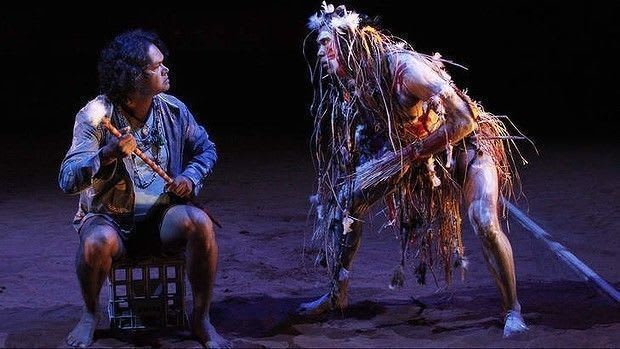

The company are on stage getting on with life until the play starts with Kamahi Djordon King coming forward, chorus-like, to explain things and introduce what he calls “a bad business, a sad business.” What follows still has the basic stories of Lear’s ungrateful daughters and Gloucester’s sons running in parallel but Gloucester is now the boy’s mother and Lear’s Fool takes over the role of faithful follower Kent.

When Lear announces he will abdicate and split up his kingdom between his three daughters while he will (still using the Folio version’s words) “unburdened crawl toward death", this is a lively, very active Lear, a bit of a song and dance man who is getting rid of his responsibilities to have a good time.

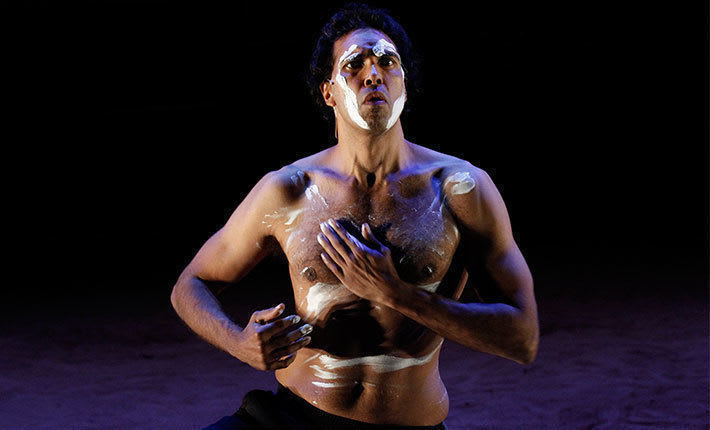

Tom Lewis’s Lear is full of himself, a flighty fellow and if he playfully plays the audience that’s his character, convinced of his own popularity he thinks no further. He’s had authority but never grown up; but you can’t help liking his infectious irresponsibility, it seems so innocent: until he loses his temper and turns to cursing in the form of indigenous ritual execrations.

Jimi Bani’s Edmund is a charismatic villain, no innocent this man, but he half gets you on his side. It’s not surprising that he can so easily con his brother whom Damion Hunter makes none too bright. This Edgar gains sense and presence when he paints his body and puts on a reed costume like some spirit of the bush.

While Lear capers around, it is Kamahi Djordon King’s authority as storyteller and the Fool within the play who gives the whole production weight, a commentator for Lear and for the audience. He still gets hanged but then comes back to life to make sure we get the production’s message.

The women make less impact, their storyline truncated. Their conflict becomes domestic. Telling your father to “piss off right out of my yard!” lacks regal authority. The Regan and Goneril of Natasha Wanganeen and Jada Albert don’t seem intrinsically evil although jealousy over Edmund makes the sparks fly and Goneril’s suicide is bloody.

While much of the detail has been trimmed out in this telling of the Lear story, it has been given an added dimension specific to its relocation. Rarriwuy Hick’s Cordelia doesn’t just cite her love for a future husband in qualifying that due to her father but also her children and the land and, more importantly, reminds her father that, “you can’t give me what you don’t own.” In Aboriginal culture you cannot own the land. The land owns you. At the end of the play, that message is repeated.

Though it may top and tail the story, it is little more than a statement. Perhaps that is enough as a reminder for Aboriginal audiences but this is the Barbican. I wonder how many performances Malthouse Theatre is giving in the Northern Territory. I know the play has been seen in major Australian cities; is there enough to put that over properly to other Australians increasingly bent on exploiting mineral resources?

This production has all the signs of being aimed at playing world festival venues. In a world obsessed by land and property values, such radical rethinking needs more explanation.

This retelling of an English “dreamtime story” is intriguing, entertaining and often moving but, though it provides an apparently happy ending, it can’t reconcile that huge difference between cultures. Making the case for adopting Aboriginal values in the City of London—will the Barbican take up that challenge?