It is more than a quarter of a century since this splendid play, inspired by papyri that provide fragmentary text of a satyr play by Sophocles, was seen at the National Theatre following its single performance première at Delphi. It is a long time to wait for a London revival of something so lively.

The action begins in Egypt in Oxyrhynchus where two Oxford papyrologist archaeologists, Grenfell and Hunt, are sorting through ancient detritus packed with papyri that their fellaheen workmen have been unearthing.

Hunt keeps finding petitions from refugees and the homeless among the administrative documents and commercial trivia but they don’t interest Grenfell who is on the look out for some unknown gem of classical poetry and drama.

Frantically manic, he thinks he hears the god Apollo demanding he rediscover a play in which he is featured. It is Sophocles’ Ichneutae (The Trackers), previously known only from a few quotations in other ancient authors. In it, the god sends a band of satyrs in search of his cattle, which have been stolen. Grenfell, becoming possessed by the sun god, does find fragments and now must fill in the lacunae and so provide us with a play.

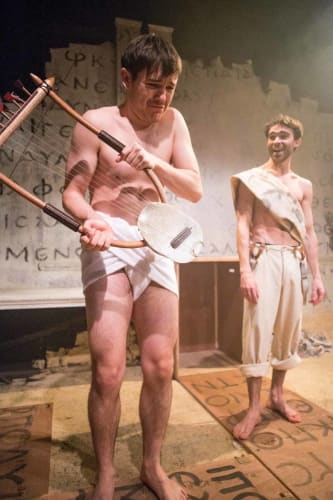

A band of clog-dancing satyrs emerge from the cases of papyri and, following the cow tracks, find the thief: baby Hermes. He has already used the guts of the cattle as strings for a new toy he has invented: the lyre. The senior god now claims that gives him ownership of it and Tom Purbeck’s resonant, powerful Grenfell/Apollo requisitions the instrument from Dylan Mason’s Hermes, mewling in his ancient Greek nappies.

This is one myth from the classical canon, though the 400 lines of the Ichneutae fragments don’t take it even that far, but now Harrison introduces another: the story of Marsyas, a satyr.

His brother satyr Silenus tells how Marsyas found the aulos, a twin-pipe wind instrument that the goddess Athena had thrown away; she thought it disfiguring to puff out her cheeks to play on it.

Marsyas became an accomplished musician. How dare he, a mere satyr. In a competition with Apollo, judged by the Muses (who of course are biased), the god wins and can do what he likes with the loser.

This sparkling comedy turns painfully tragic as Richard Glaves’s Hunt, who now become Silenus, describes the horrific process of Marsyas’s flaying in graphic detail.

Purbeck and Glaves both give powerful performances that could carry in an ancient Greek amphitheatre but are so rooted in character they aren’t out of place in the Finborough’s small space, vibrating like the clamorous clog dances of this fine chorus of satyrs. They match the irresistibly appealing pattern of Tony Harrison’s poetry with its bold rhymes and muscular rhythms.

Jimmy Walters’s production fits a full-blooded production into a small space. It bursts into our consciousness without feeling cramped. In classical times, satyr plays followed performance of tragedies, offering social satire and lampooning public and political figures. Here Harrison offers a critique of cultural elitism, of the split between “art” and popular entertainment, that the hoi polloi can’t appreciate the finer things.

Perhaps in the last quarter century our culture has become more widely embracing, but growing income streams increasingly restricted ability to pursue cultural interests and entertainment.

Theatregoers going to the National Theatre to see those 1990 performances passed a cardboard city, housing the homeless. Those papyrus petition pleas were still unanswered millennia later, street sleepers may have migrated to other parts of London but they are still with us and refugees are still a world problem. Sophocles would have found his play still entirely topical.

The Trackers of Oxyrhynchus is hard-hitting stuff but it comes with wit and hilarity and a fine sense of what makes good theatre. It is great entertainment.