Two years since its inception, Woolf Works returns, with Alessandra Ferri and the original cast mostly intact bar injury and illness, to celebrate its creator’s, Wayne McGregor’s, decade anniversary as resident choreographer with the Royal Ballet. There is now an option of a second cast with Mara Galeazzi in the lead, which would be worth seeing, too.

I think I see changes in the last section of the triptych, a simplification perhaps. Is memory playing tricks? Woolf is all about memory and time and language—capturing that in dance is like walking on air, and McGregor leans towards space oddity.

McGregor, whose mind is famously inquisitive, and his range of interests broad, and his dramaturg, Uzma Hameed, go with an allusive response to her work, which of course has its own pitfalls.

Speaking to audience members, I find some are there as Virginia Woolf acolytes; some for McGregor; some just like going to the ballet. One mature gentleman is seeing it for the sixth time, but he wishes there were short synopses and an idea of who the characters are—they are not named in the programme. Though the programme does give a sense of Woolf with lines from her stream of consciousness works and prints her 1937 BBC broadcast, which we hear in the opening moments.

I wonder what those who don't know Woolf’s work are seeing—bodies projected in space (the dancers are outstanding in stamina, contortion, style and dedication), a Gesamtkunstwerk with almost equal weight given to Lucy Carter’s laser light show, Max Richter’s cinematic score, Moritz Junge’s costume design, Ravi Deprees’s film design, Ciguë, We Not I, and McGregor’s overall designs and choreography.

But one can’t undo what one knows and those who know Mrs Dalloway (1925), Orlando (1928) and The Waves (1931) will be trying to put flesh on the three half-hour bones.

The first panel of the triptych, I now, I then (Mrs Dalloway), is the most evidently expressive of storyline. Ferri is both (I think) Dalloway and Woolf looking forward and back, remembering golden days in the garden. Selves splinter, the young and the old overlap. Don't we carry both in us?

Ferri and Beatriz Stix-Brunell as the younger self; Federico Bonelli (Peter Walsh her former love) and Gary Avis (dependable Richard Dalloway—in tweeds he makes me think of Enigma Variations); Francesca Hayward (Sally) a brief love affair that Woolf/Dalloway remembers with a smile.

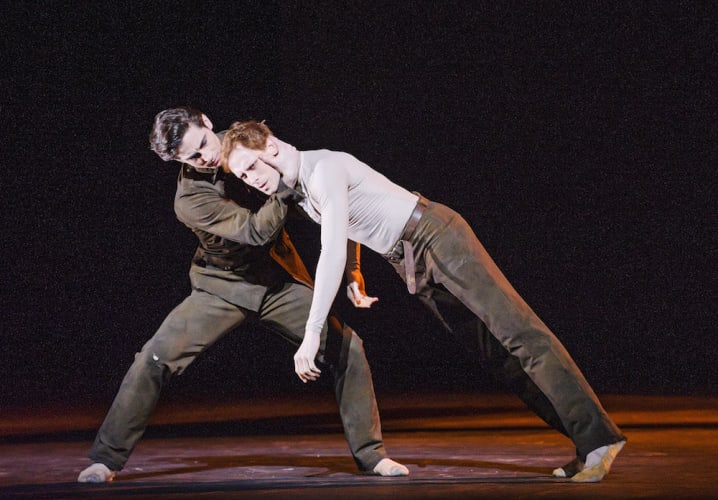

But all is not well. A parallel story unfolds, that of a traumatised soldier, Septimus, who can’t settle with his wife, as he remembers the intensity of life at the front and his fallen comrade-in-arms. Edward Watson gives an anguished angular performance in duet with Akane Takada and Calvin Richardson. There’s a storm in his head.

A fractured video montage plays on the three Stonehenge-like moveable wooden frames: London in the twenties, Big Ben, men in hats, captured street noises and captured time. Her words scroll on the scrim. Characters are watchful. The past and the present collide in Richter’s music, electronica and orchestra strings, in Philip Glass propulsion. But Ferri dances to her own time, her own inner lyrical pulses, in ripples of movement.

Elegiac, sensual, and melancholy—Bonelli and Ferri make a fine couple, but it’s to Avis’s safe hands that she returns. Wonderful dancing from all, and some lovely slow movements—a departure from McGregor’s usual hectic pace and warped physicality.

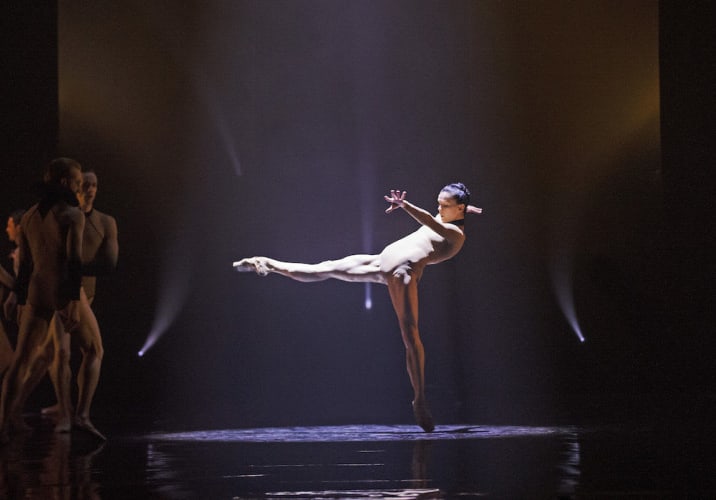

The next panel, Becomings (Orlando), steps up several gears—to Richter’s spacy club sounds. We’re back in McGregor’s familiar avatar headspace. Did I read that Blade Runner is his favourite film? This makes sense if it is. Solaris comes to mind, too. Replicants in golden metallic Elizabethan costumes and black ruffs, which they shed gradually as time goes by till they are specimens in flesh-coloured bodysuits.

Emotion-free Artificial Intelligence has reprogrammed Woolf in cold cold cold space. Lasers play and disturb the galaxy—on stage and in the auditorium—Close Encounters.... Relativity, space and time travel.

The dancing is dynamic, gymnastic: Natalia Osipova is unbelievable, but then they all are, too many to mention. McGregor is trying for the speed of light. A dozen dancers flash and skid like meteors across the stage, dance duets, change partners. Which one is the Fool? Bendy shape-shifting people… And overload.

The final panel is about life’s trajectory and its finality: Tuesday references both Woolf’s suicide note and The Waves, the symphonic novel she called her ‘play poem’. Ferri returns to bring it to a close.

A monochrome back projection of slowed down waves—I hope taken in St Ives where she spent many a happy childhood—swells overhead (it evokes Paul Nash’s 1925 Winter Sea (Dymchurch) for me). Six children in black leotards play underneath it—the six whose life stories interweave in the book.

Adults take their place and multiply till two dozen, all in black with facial jewellery—filigree masks that dehumanise—fill the space in addition to the very human Ferri, Bonelli and Sarah Lamb.

En masse they pay repeated reverence to the four corners of the earth. They fade away and Bonelli (black tights and bare torso) lays Ferri (skimpy black shift) down. Woolf drowned in the river Ouse and her swept away body was not found for three weeks.

Voices (soprano Anush Hovhannisyan sings gently) and sea sounds mingle. Gillian Anderson’s soft voice reading the suicide note loses out to the sea. Ferri and Bonelli seem happy together—Woolf’s note to her husband said as much.