“How much do you want for them?”

“I really don’t know... I have never yet traded in dead folk.”

A stranger has arrived in town. Urbane, well-dressed, charming, Chichikov is travelling through rural Russia, staying at the choicest inns and dining at the best tables; indulging in slick sales patter to persuade the local landowners that he can save them a fortune by relieving them of the burden of an irksome tax legacy.

Chichikov is a confidence man with a plan: if the miserly, drunken estate holders sell him their ‘dead souls’—the serfs who have died since the last census—they will no longer have to pay the taxes on these non-existent people. By transforming the worthless, fictitious serfs into something of ‘value’, as a man of paper ‘property’ he may raise a mortgage and acquire real estate—and real serfs.

In manipulating corrupt Russian bureaucracy for personal gain, Chichikov finds himself infected by avarice and ambition—as ‘sick’ as the country that he exploits. Gogol’s unfinished novel, Dead Souls, adapted here by Chloë Myerson, is not simply a satire on the injustice and absurdity of mid-nineteenth-century Russian society and the foolish banality of everyone from richest aristocrat to the dullard peasant. It’s also exposé of the contradictions within an individual and a commentary on human complexity.

Chichikov is an ‘acquirer’—a very ‘modern’ entrepreneur whose gods are consumption and commodification but whose capital is ‘dead’. He is comic and rancorous; greedy and pragmatic. And, as Myserson and director Nico Pimparé’s experimental presentation make clear, he is no less familiar today.

Ironically, perhaps tragically, recently Russian events confirm this all too clearly. During the 2003 Moscow-sanctioned presidential elections in Chechnya, one of the fifteen presidential candidates—State Duma deputy Aslambek Aslakhanov—doubting the results of the ‘population census’ conducted in Chechnya by Putin, discovered 200,000 ‘dead souls’. Prior to that, in October 2000 Amelia Gentleman reported in the Guardian that a provincial civil servant in Kolomna, a small town 100 miles south-east of Moscow, had been arrested for inventing 250 dead citizens to claim funeral grants from the government, defrauding the state of 330,000 roubles over two years by persuading impoverished citizens to sell her the rights to fabricated dead relatives in order to collect their burial allowances. Plus ça change.

Myerson hits closer to home, though, as her drama—ostensibly, so video surtitles tell us, sited sometime during the 1800s—spills into twenty-first-century London. The use of live video feedback makes both the audience and the patrons of the pub beneath the theatre complicit in Chichikov’s schemes and Russia’s inequities. Or, perhaps Myerson is suggesting that we ourselves are the ‘dead souls’, essentially worthless but ripe for exploitation. There’s some spontaneous interaction as audience members are asked to hold characters’ jackets or provide a slurp of beer.

In fact, I found the parallels that the play draws between past and present simultaneously too obvious and too imprecise. Gogol’s detailed, realistic representation of a Russian pastoral town in 1842 is historically specific. He dramatizes the threat to unyielding, undemocratic feudal institutions at a time of socio-economic restlessness: the emancipation of the serfs lay less than 20 years ahead, and industry and capital markets were beginning to develop, as a result of Western influence.

Myerson’s script points at manifest contemporary congruences: social inequality, state inefficiency and self-serving subterfuge are hardly the prerogatives of history. But, her dialogue does not always find an appropriate equivalent for Gogol’s hyperbole, as he exaggerates the faux politeness displayed by the Russian townspeople which masks their mendacity. The register of Myerson’s script is at times too brusque, even crude, the tone lacking the necessary patina of false civility and respect deployed by the most ruthless swindlers.

The video captions do, however, provide a modern match for Gogol’s ironic narration; the Russian writer’s narrator, spurning omniscience, intrudes into his own tale to comment on characters and even, at one point, to profess to know what the furniture is thinking. The on-screen text neatly mimics this self-knowing sarcasm.

I was less enamoured of Pimparé’s ‘Machine’—a ‘cardioid condenser microphone’ linked via a sound-mixer to a PA whose output causes a crash cymbal to vibrate. Though its hum—or twanging screech—evokes the eerie echoes of the dead, the actors were not equally adept in employing the central-hanging device, often speaking too fast or too close to the microphone, resulting in ear-irritating distractions and obfuscation.

The central issue of ‘class’ was deftly communicated, though, not just by accent but also by dress: Chichikov’s ragged shirt, concealed by a cheap, shiny jacket, contrasted with the landowners’ luxurious attire—Plyushkin’s silk dressing-gown and Nozdryov’s peacock shirt and shiny black shoes.

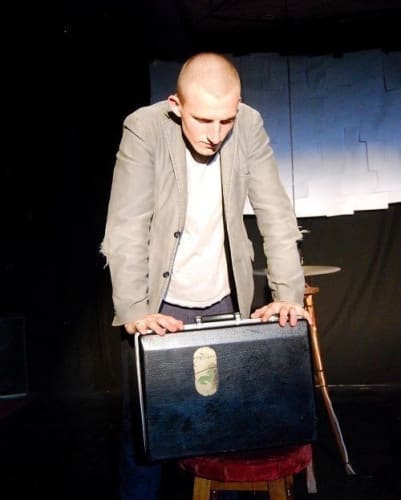

Joshua Jacob was disturbingly intense as the conman with self-conviction, evincing a desperate intent bordering at times on madness. But, I felt that Chichikov would need more charm and suavity to convince his dupes to hand over their futile ‘heritage’. He’s a man who denies definition, as Gogol’s evasive introduction to his protagonist confirms: he is ‘not handsome’ but ‘not ill-favoured’; not ‘over-fat’ and not ‘over-thin’. A suave surface must conceal his duplicity, just as his black briefcase—a ‘treasure chest’ in Gogol’s original—contains a secret compartment concealing the money required for the acquisition of oppressed ghosts.

Toby Osmond’s Nozdryov has something of the boundless optimism and innate sense of privilege of Chekhov’s Boris Simeonov-Pischik; his unscrupulousness, compulsive lying and obsessive gambling were enhanced by Osmond’s strong comedic timing. His ridiculous wrangling over a price for something that it palpably worthless, and his absurd determination to throw in a carriage and a barrel organ—not a German beggar’s hurdy-gurdy but a mahogany specimen—retrieved some of the rich characterisation and keen insight of Gogol’s novel.

Jules Armana was a more sober Sobakievitch and his ridiculous fisticuffs with Chichikov over the price of the dead souls painfully highlighted the question of the price society accords the living and the dead. But, inevitably, a 90-minute adaptation cannot embrace all of Gogol’s philosophical questions, and Myerson offers few intimations of what the ‘dead souls’ might ‘mean’ or represent: do memories of the dead have ‘value’? Moreover, Armana did not distinguish sufficiently between Sobakievitch and Plyushkin, and his Prosecutor was not imbued with the requisite menace of the town’s growing suspicion, such as is necessary to convey the sense that Chichikov is being pursued.

At the end of the first part of Gogol’s novel, Chichikov flees the pastoral town in his carriage; Jacob’s Chichikov surges down the stairs onto the Balham streets, doggedly clutching his briefcase of souls. Nozdryov’s closing polemic ‘spelling things out’ is superfluous: capitalism breeds exploitation, which erodes the humanity of the manipulator and the mis-used alike. Horse-drawn carriage has given way to corporate jet; ponzi schemes have replaced dead souls. There are many more Chichikovs thriving today.