Rufus Norris doesn’t leave the National Theatre for another 18 months or so, but one imagines that the board are already firming up the process to recruit his successor, if they haven’t actually set it in motion.

Norris has been extraordinarily unlucky to find himself running the country’s leading theatre in the middle of the pandemic. If that wasn’t bad enough, he has also had to face the deprivations of a government that has no apparent investment in the arts, despite its desire to appoint new culture ministers every few months. The problem here is that those ministers never seem to have any interest in culture, let alone a passion for it.

Indeed, there is some irony that the Minister who caused most damage became the central figure in a mini-scandal due to her unwillingness to resign as an MP, despite taking pay without appearing in Parliament or meeting the needs of her increasingly frustrated constituents.

In the future, Nadine Dorries will probably proudly point to her success in destroying the English National Opera and emasculating so many other companies including the National, from the grave as it were, since she wasn’t even culture minister when her most ridiculous cuts were implemented.

Many theatre companies are consequently struggling with inadequate budgets, meaning cuts to staffing and reductions in the quality and quantity of programming.

In this light, it seems worthwhile to consider what the new Artistic Director at the country’s National Theatre could do if he or quite possibly she really wanted to scope up to a programme worthy of the institution’s title and history. I fear that, although they are radical, none of the choices will seem attractive.

It is possible that, by the time of Norris’s departure in 2025, we will have a new government that is more sympathetic to the arts but, given the country’s sinking economy, willingness and ability to fund the arts may not coincide for a few more years.

In an ideal world, the National Theatre would combine large-scale renditions of the classics together with new work. That could also be epic, as proposed by the Monsterists in a manifesto that is now practically forgotten but wished to give playwrights scope to write large plays on big topics with sizeable budgets (I trust that they will forgive the paraphrasing).

Over the years since its inception, the National Theatre has faced financial problems for assorted reasons and always got by, though too often it was forced to cut back on its primary mission in order to stay solvent.

When he was Artistic Director, Trevor Nunn came up with a magic formula to protect two of the stages, largely at the expense of the third. This was to programme large, popular musicals designed to run for months if not years at close to 100% capacity in one of the large spaces. This would bolster the bank balance (or more realistically reduce the overdraft) but showed a distinct lack of artistic adventure.

This recipe has, somewhat ironically, helped the RSC, which must make a significant proportion of its income from global productions of Les Misérables and Matilda, neither of which has anything to do with Shakespeare.

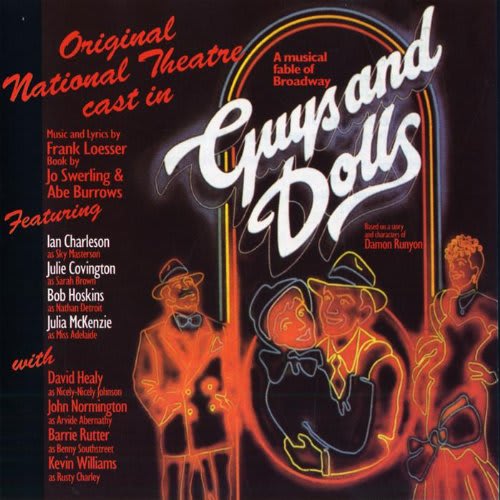

More recently, Sir Nicholas Hytner has changed policy at the Bridge by filling the theatre for a year or more with a universally popular production of Guys and Dolls. This is great news for the producers, but sadly doesn’t help playwrights, directors or actors who might have had opportunities to fill the stage for a month or two with regular turnover of new work or revivals.

If the musicals route doesn’t appeal, another option might be to ramp up ticket prices. Nobody ever seems to have asked the question, but many straight plays in the West End have tickets that now cost in the region of £100, while best-selling shows charge even more and most popular musicals seem able to wring £300 a ticket out of rich corporates and tourists. In that context, perhaps our National Theatre should look at charging on a more commercial basis.

This might sound like a denigration of their community ethos, but combining expensive tickets for rich people with subsidised tickets for those who cannot afford more could be a way forward?

Finally, if the aim is to achieve an optimum commercial position, there is a much simpler solution, which is to follow the example of so many sports.

I have little doubt that the Qatari Sovereign Wealth Fund or the Saudi Arabian Public Investment Fund would welcome the opportunity for a little bit of culture washing on the cheap. If they are willing to plough billions into football and golf, then a few tens of millions directed towards a theatre that could bear the relevant fund’s name would be small change.

While NT has been used for this mini case study, with appropriate adjustments, the principles could apply to almost any other theatre company in the country.

Most readers will probably regard everything suggested in this article as unacceptable and should do so. The proper solution would be for the government to fund the arts adequately, but who knows if or when this is ever going to happen again.