Federico García Lorca’s short play, Amor de Don Perlimplín con Belisa en su Jardín (The Love of Don Perlimplín and Belisa in the Garden) is not as well-known as the playwright’s acclaimed masterpieces, such as Yerma and The House of Bernarda Alba, but this bilingual production at the Cervantes Theatre suggests that it ought to be. It shares with those later plays meditations on reality and illusion, love and the imagination, desire and its frustration, and uses the poetry of the theatre to challenge social principles and prejudices.

Don Perlimplín is more abstract, however, and at the same time more whimsical. Lorca subtitled the play "aleluya erótica en cuatro cuadros (versión de cámara)", an ‘aleluya’ being a popular form of literature that was a precursor to contemporary comic-cartoons, though the name originally described holy cards distributed at Easter expressing joy over the resurrection—a not irrelevant point, given the Christological references and associations that the text contains. Don Perlimplín—an eighteenth-century bachelor, ugly, bookish and naïve—is a typical ‘aleluya’ character, but also reminiscent of commedia dell’arte archetypes. Indeed, Don Perlimplín is an eclectic blend of different theatrical and literary genres and traditions.

At the Cervantes, director Paula Paz skilfully shapes and paces the movement from initial farce to concluding tragedy. The prelude and three short scenes form a coherent, evolving sequence. Though there is no set, detailed costuming does the work of establishing the puppet-like ambience of the opening, the characters seeming to represent aspects of human nature rather than being endowed with psychological complexity. The characters seem ‘known’ to us: Don Perlimplín in his dressing-gown, Marcolfa in her servant attire, Belisa’s mother luxuriously fetching in formal dress—though we don’t have the grandiose wig full of beads, ribbons and stuffed birds for which Lorca calls!

Gradually, however, we begin to question the eponymous Don’s motivations and emotional experiences, and this transition is encouraged by the bilingual production which presents the first half of the play in Spanish (with English surtitles) and the second half in English (translation by Caridad Svich) with two casts, each part with its own separate staging. The eighteenth century becomes the present, the artificiality of whitened faces gives way to modern naturalism, and Perlimplín’s love transmutes to become yearning not for a young woman but for a young man. As the casts intermingle, we are encouraged not only by Lorca’s text and theatrical devices to question our assumptions and perspectives, but also by the very nature of the performance itself.

The plot seems straightforward. Don Perlimplín is a fifty-year-old ‘child’ who has eschewed marriage and is looked after by his housekeeper, Marcolfa. The latter bossily urges him to marry: what will he do when she is too old to look after him? She encourages him to approach his beautiful young neighbour, Belisa, whose mother shamelessly compels her to accept the old man’s proposal. After all, he has land, sheep and goats, which he sells at market and his money will make her even more beautiful!

Perlimplín has never experienced love, but a glimpse, through the keyhole, of his wife-to-be’s naked body as she dresses for their wedding inspires a lust and love which are almost spiritual. Belisa, however, is all carnality. On their wedding night, ignoring her new husband, she welcomes five different lovers to their bedroom. Don Perlimplín accepts his cuckolded state but, his imagination now released, begins to become the author of his own play, in order to enable Belisa to experience feelings beyond physical desire and in the hope that she will reciprocate his own love.

Thus, a mysterious red-caped man begins to appear beneath the balcony of his house, writes Belisa exquisite letters about her body, but refuses to reveal himself. When she confides in her husband about her love for this stranger, Perlimplín tells her that she will meet the mysterious lover in the garden that evening.

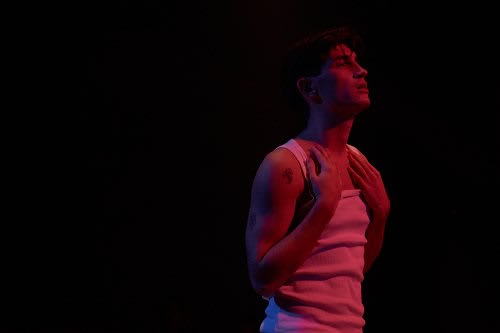

Paz’s direction respects the lyricism of Lorca’s play. The characters’ movements across, and into and out of, the stage space have grace and fluidity. Although the performance does not incorporate the music and songs that Lorca integrates into his text—for example, the song which introduces us to Belisa and through its erotic imagery confirms her brazen awareness of her sexual body; or the lyric that Perlimplín sings when he realises that Belisa’s body has awoken love in him, a love that has mortally wounded him—music (Lex Kosanke) is used to enhance the manipulated movements of the characters within and between scenes and, alongside some striking chiaroscuro lighting (Sammy Emmins), to create moments where characters’ inner lives are intimated or illuminated.

Juan Carlos Talavera is our initial Perlimplín, hectored by Maite Jiménez’s earthy, resourceful, Marcolfa. He’s a nervous suitor but solicitous husband, and later a resigned cuckold. But, by the end of the first scene, there are also intimations of the pain that he feels as a victim of a love until now not known, and of the passion that will swell when he becomes Belisa’s fictional lover. Talavera, and subsequently Paul Rider, creates sympathy for a character who, in a simple farce might only invite ridicule. We have a sense of a man out of step with his world, something that is emphasised by the shift of staging in the second half of the play.

And, more than this, we sense an emotional complexity that we cannot quite grasp, as Lorca keeps things from the audience. In scene 2, which takes place in Perlimplín’s dining room, there’s a change of dynamic between master and servant. When Mary Conlon’s Marcolfa chastises the Don for accepting his public humiliation, he takes charge of the situation, and subsequently his exchanges with Belisa are more teasing and assured.

Effectively ‘sacrificed’ by her mercenary mother (Montserrat Roig de Puig), Maggie García is a haughty, solipsistic Belisa, appearing at first half-naked, aware of her own beauty and of the desires of her body. She moves with the grace and balance of a dancer, her physical gestures elegant and eloquent. Because of the sparse set, we perhaps miss a little of Lorca’s ritualised treatment of her love affairs—those five whistles, five open windows, five ladders to the ground and five hats beneath the balconies, which confirm to Perlimplín his misfortune. But, both García and Álex Pérez convey Belisa’s absorption by her / his / their physical being and desire, and the startling transformation of illusion into truth that occurs at the end of the play is powerfully presented in all its elusive complexity.

I saw that opening night performance, which was not the official press night. At this early stage in the run, I felt that if there is one aspect of the production that is less successful, it’s the presentation of the two ‘sprites’—an archaic feature of long-standing theatrical traditions, which Lorca uses as a technical means of provoking the audience—who intervene during Perlimplín’s wedding night. It’s worth remembering that Lorca started writing the play as a rhyming puppet farce, and the intervention of the sprites reminds us of these self-consciously theatrical and stylised origins. He instructs that they should draw a veil across the stage so that the audience cannot see Belisa’s deception of her new husband.

It’s a crucial turning point in the play, for here, Lorca complicates our perception of Perlimplín as simply a cuckold and begins to deepen our awareness of his motivations. The sprites speak directly to the audience—seated, he instructs, upon the prompt box—alluding to the nature of the Don’s troubles and teasing us that it is necessary to cover things up so that they can be discovered. In this way, Lorca implicitly attributes to the audience the role of ‘society’ with its standard moral principles and responses, but challenges us to question those principles and prejudices, even as we ridicule Perlimplín.

Paz doesn’t quite capture the import of the sprite’s brief exchange. We don’t have a veil across the action, though lighting does its work, and the words, delivered by the young actors Maya Kalundu and Jada Kalundu, don’t pack quite enough ironic punch or mine the satirical equivocations of the dialogue. The sprites are not a trivial motif.

However, the director does craft and control the slide from farce to tragedy with sensitivity and insight, communicating the lyricism of Don Perlimplín’s illusions and imagination and the ambiguity of his final sacrifice.