Marking Rambert’s 90th anniversary, this is a triple bill of recent choreography commissioned by Rambert from artists who had all been dancers with the company.

It opens with Flight, choreographed by Malgorzata Dzierzon to a score by Somei Satoh, that encloses a central section specially composed by Kate Whitely and is performed against a wall of mobile panels on which video by Luke Halls is projected.

The susurrations of the very Japanese sounding opening see Edit Domoszlai stretching on the floor, isolated and trapped by the barrier until a panel opens enough for Miguel Altunaga to slip through. A flurry of what could be butterflies appears over the tilted architectural images of the projection, the numbers increasing until they could be a mass of migrating locusts.

But this is not so much about animals as people. The first couple are joined by many others, pairs dancing with a tension that could be about parting, whether from people, from place. Two single figures express the same feeling while the couples all freeze.

Later, the wall panels form into a rotating set of compartments. A crowd pressing into one section suggests illegal immigrants crammed into a freight container, others are alone and seem in a struggle for survival or may break free into space while, as they all move into free space, the images resolve into upright architecture with stairs that lead upward. In a final section, danced here by two female dancers (though the choreographer says they could be any gender), makes dramatic use of shadows. This is a ballet that is full of tensions but given a remarkable fluidity.

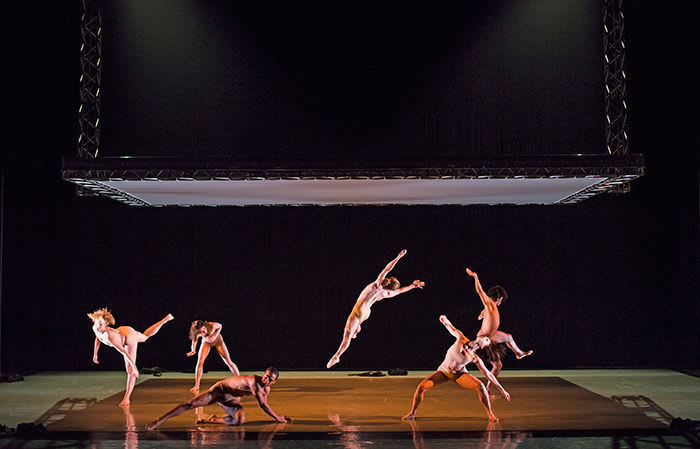

Frames is set in a box of greenish fabric within which Miguel Altunaga is lying, rolling, leaping and bending using a long strip of metal sometimes like a vaulting pole, sometime to extend his reach or enfolded almost in a caress. He is joined by the rest of the company, who bring in more metal poles.

Alexander Whitley uses these rods as an essential element of his choreography, an extension of limbs and a limiting device at the same time as they dance to Daniel Bjarnason’s pounding, rhythmic music. Designers Revital Cohen and Tuur Can Baten collaborate with Whitley to devise multiple shapes into which these metal poles can be formed. Their shapes are continually changing: sometimes an archway, at one point a series of ballet barres. There is a defining of space, like the box of lines used by Francis Bacon is many of his paintings, and a flowering of forms with which the dancers interact that is fascinating to watch. Sudden swishes of a dancer’s blonde ponytail resonate against the framing outlines.

Small lights attached to fixed frames create one sequence when, lit only by them, visibility is determined entirely by their light as the frames are manoeuvred. Brief glimpses of performers out of darkness are cut into by bright illumination. That section is slightly too long and becomes repetitive, but this is a work of considerable invention: the dancers form the shapes but the structures then direct their movement.

In a final movement, the poles form an overhead structure and the floor is left open, the dancers free. This is a work of compelling choreography that makes everything as impermanent as the dancers’ movements, lost the moment it changes.

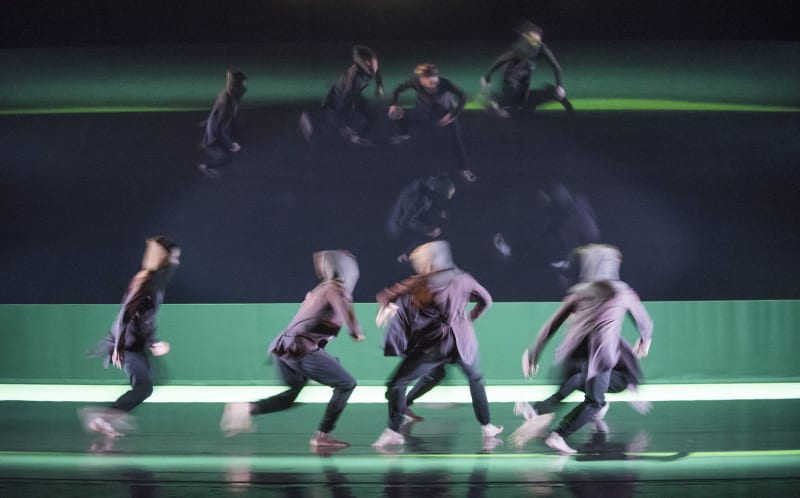

Hydrargyrum starts in darkness and is danced to music by Aleksandra Vrebalov in a setting by Jon Bausor that creates constant flux. Choreographer Patricia Okenwa first offers us a group of hoodies gradually emerging from the darkness. They look like a street gang in confrontation. There are only six dancers but they seem more, such is the energy. Above them hangs a huge panel that blocks all light until it starts turning, allowing a streak of light on the stage floor and its top edge reflecting the orchestra in the pit to the first circle audience; others will see something different according to angle, while as light increases the dancers are also reflected above.

One figure asserts independence but is forced back into the gang, allegiances alter, there are new confrontations and the music’s electronic beat is increasingly discordant. The panel above has turned and now it begins to offer its white underside; the figures are touched by a pinkish light and they begin to disperse. One dancer downstage throws back her hood and slowly divest herself of her tracksuit. Another opposite follows suit and soon they are all looking naked, bare except for flesh coloured briefs and bras, and dancing more freely, almost wildly.

Hydrargyrum is an old name for mercury. It can be quicksilver with all its sparkle, volatile and poisonous. But what does it mean here? Is this like a broken thermometer, its metallic fluid running free? Youngsters released from the constraints of gang peer group asserting their own individually? Is this the pink glow of happy freedom? There was also a feeling that this red glow could be Hell too.

However an audience choses to read these ballets, they all offer engagingly watchable dance and show off a company of excellent dancers.