It was here, in Southwark in December 1170 at the priory church then known as St Mary Overie (“over the river” to distinguish it from the many North Bank churches with the same dedication), that Thomas Becket, newly returned from exile, gave his last London sermon and, when he was being welcomed by its canons, a mad woman called Matilda is said to have caused a disturbance shouting, “Archbishop! Beware the knife”. Before the end of the month, he had been murdered in Canterbury Cathedral.

In 1212, fire destroyed the church that Becket visited, which was then largely rebuilt, but it still seems an appropriate place to stage Eliot’s play about his martyrdom in a production which it is planned will tour British cathedrals next year to mark that event’s 850th anniversary.

Becket, a commoner raised to high office, had been a close supporter of Henry II as England’s Chancellor but, when the King thought to secure the collaboration of the Church by appointing him Archbishop of Canterbury, things went wrong: Thomas resigned as Chancellor and took his new role very seriously, challenging the King by rigorously defending the rights of the Church.

Eliot’s very formal play, a mixture of verse and prose, which begins when, after seven years abroad but the King now claiming to be friends again, Becket, still uncompromising, returns to Canterbury. A group of women, who comment on the action like a Greek chorus, express their foreboding and when Becket arrives he already seems to be embracing the idea of forthcoming martyrdom.

Eliot is more interested in exploring the struggle in Becket’s mind than the drama of violence. He shows the Archbishop tempted by four courses of action: backing off for his own safety, following the King’s wishes and gaining more power and more wealth, joining the barons who oppose the King and want to limit his power or seeking the glory of martyrdom.

It is the last that he recognises as the most challenging: “the greatest treason: To do the right deed for the wrong reason”. He has to question his own motivation before deciding on his action.

Whilst the dark shadows of the cathedral with soaring columns, plainsong, processing monks, candles and the glimmers of light reflected from gilded figures on the reredos and the decoration of Gower’s tomb all contribute to the atmosphere, the setting has its disadvantages.

The audience is seated down the whole length of the nave; distance and a flat floor don’t make it easy to see everything. Director Cecilia Dorland makes entries through the whole length of the church and the chorus especially range round the side aisles to bring the action closer to everyone, but that doesn’t help deal with the building’s acoustics. It is a problem often found in church settings which were designed for services sung in the choir and congregations would not have understood the Latin liturgy anyway.

If someone is close and speaking towards you, you catch what they say as they go past but much was only patchily comprehensible even from a seat only a few rows back.

(Though a handy hassock used as a cushion gave a more comfortable seat and a slightly better view.) Some in the audience appear to have heard well: experience will vary according to location of seat and of action. The use of radio mikes possibly added to the reverberations, but delivery certainly needs to be carefully matched to acoustic.

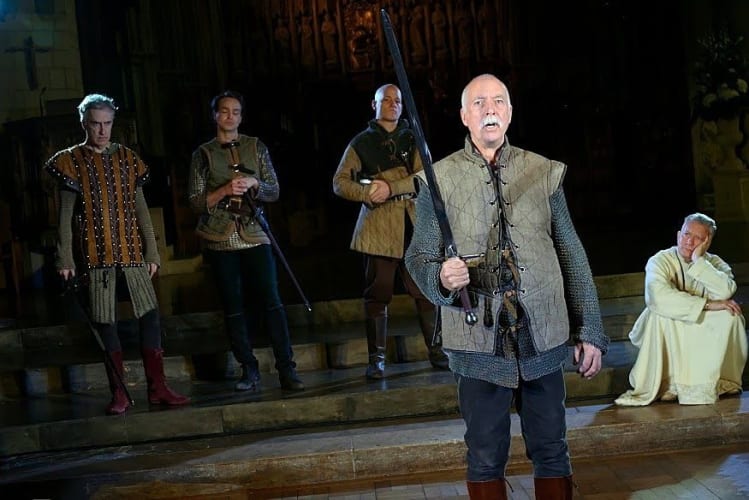

While more florid voices left only emphasised words distinguishable Jasper Britton’s more natural and slower delivery was much clearer. He gives a sensitive performance and delivers the central Christmas Day sermon (of Eliot’s invention—the original is not recorded) intelligibly as he discusses the idea of Christian Peace and the concept of the martyr. It is a speech greatly influenced by when it was written in 1935 when Fascism was gaining adherents and war clouds already looming.

All the performers in this cast show considerable commitment but from where I was I could understand only intermittent lines from the chorus and not much from some others in the cast. I did hear Isaac Deayton’s brief appearance as Messenger, some of the younger priests and fortunately Rupert Bates, Pip Brignall, David Keogh and David Shelley when presenting the murderers’ self-justifications in the epilogue that Eliot offers.

A qualified commendation then. If you’re going to see it, wrap up, it seems as chilly as outside, and if there isn’t someone shorter behind you make use of that hassock!

When this production goes on tour next year, I hope it will be possible to more closely fit voices, their pace, projection and placing to each location. Eliot was a great poet (if not such a great dramatist) and you do need to hear his words.