This triple bill opens with Itzik Galili’s A Linha Curva, a work inspired by the Brazilian carnival that offers a stage full of dancers, the company amplified by performers from the Rambert School, and bursting with energy.

An image of dancers in shiny white ruffs is almost instantly replaced by rows of dancers: Galili makes his lighting part of his choreography. Thrusting hips and waving arms have a samba and capoeira exuberance synchronized with mechanical precision.

There is a sudden change to very slow stretches and turns and then it is back to high energy: a chain of dancers in unison, lines through which prone bodies glide through on skateboards to the sound of four drummers an a vast array of percussion pounding out Percossa’s music.

It is part-party, part-ritual with elements of capoeira competition but the mechanical overweighs the exuberance, surely this should feel more joyful. It has been in the repertoire since 2009 (though this is the first time I’ve seen it). I wonder did the dancers once find it more fun?

There’s a clever sequence with the chattering rhythms of the Balinese Kecak, the monkey dance, the men springing in leaps like deep pliés, hands in see, hear and speak no evil positions, but it just misses being witty. While responding enthusiastically to the rigorous vitality of this audience pleaser, it didn’t generate that feeling of happiness that seems its potential.

The other two works are new ones, premièred this autumn and here getting their first London performances.

Andonis Foniadakis’s Symbiosis is danced to music composed by Ilan Eshkeri: The Heart of Creation. He has named its four movements but it’s not clear how the choreography relates to their titles. Foniadakis has said that since the Greek crisis his work has reflected its uncertainties but that that translates here into an expression of urban energy, the pulse of the street with its encounters.

There is some of the same franticness of Galili’s ballet, though with much greater fluidity, but it also reflects its title. There does seem to be a real symbiosis going on: a link of dependency between groups of dancers. Sometimes it is a correlation between dancers upstage and downstage of the grill-like screen of the setting; sometimes it is in the contact between the dancers or the way a group interact.

Dancers negotiate the angular busy chaos like pavement pedestrians avoiding collisions on autopilot. It is another ballet that demands perfect precision from its performers to avoid its swirling and whirling wild interactions becoming disasters. Its complex conjunctions, lifts and wild leaps finally resolve into two concentric circles and then just one dancer. It is an exhilarating abstraction.

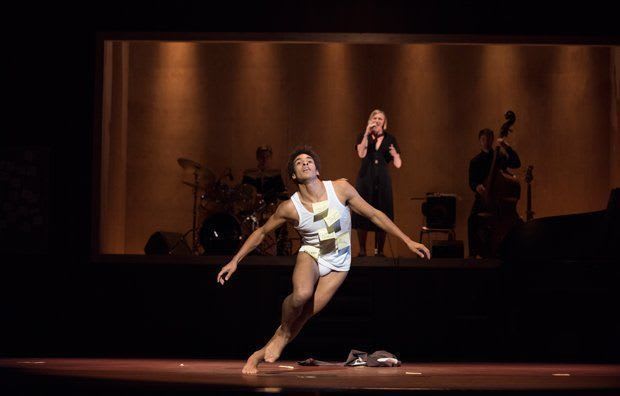

Goat, a brand new work from Ben Duke, uses an arrangement by Yshani Perinpanayagam of songs from the repertoire of Nina Simone, beautifully sung here by Nia Lynn. Duke doesn’t just do dance. He starts off with Miguel Altunaga as a sort of commentator / interviewer addressing the audience before the performers are ready.

There is a television camera following as he questions the dancers about what they are doing and that also shows action into close-up. There are sly digs at what dance presumes to portray, different attributions being made for the same steps: “addiction” says one, “betrayal” another while a third claims it’s all about injustice. “I wouldn’t have got that,” the interviewer comments.

Duke has called the piece Goat but it is should really be Scapegoat, a creature loaded up with the bad things in life that we want to get rid of. They are named on a flurry of Post-it notes stuck to the one chosen to be it. A victim straight out of Stravinsky and Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring, a Chosen One who is a sacrifice expiating sins and banishing bad things by dancing until there is no life left (shades of Albrecht here too, though this guy seems guiltless).

A blindfolded girl first selects the scapegoat; her hands explore bodies until her choice is made. Liam Francis dances the unlucky one, who seems accepting as the ritual progresses. Hannah Rudd is the girl who has to part from him in a touching duet.

The commentator crassly asks how long it will take to dance to his death and gets the answer, “I don’t know. I’ve never done it before.” But perhaps this media man isn’t without feeling. For, when all is over, he offers his clothes to the victim. Is this part of the story, a coda? Is he a last gasp replacement, or set up as the next victim, or something outside the story?

However you interpret, it makes a compassionate ending to a piece that bridges genres without effort, prods the pretentions of the arty, critiques the media and also delivers real feeling. In its simplicity, it is fully engaging but more dance would be welcome and I would happily see this work become longer.