I have had a soft spot for Samson et Dalila ever since it was one of the first presents my future wife gave me. The recording of James King and Christa Ludwig thus became a prized possession.

That was on LPs from 1973, so I never saw the production, but judging from the illustrations, it was a thousand Middle Eastern miles away from Richard Jones's modern-dress version for Covent Garden nearly 50 years later.

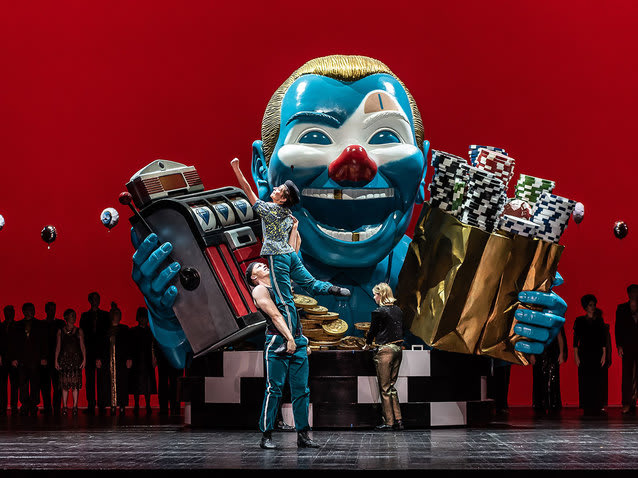

His Philistines are a bunch of puerile, vicious, cynical, murdering louts. Saint-Saëns gave them appropriately shallow music, which the designer matches with a model of their god Dagon represented by a huge, hideous, grinning one-armed bandit showering money.

I was not entirely convinced by this latter device, which introduces in the finale a theme of avarice hitherto unhinted at in the rest of the show. More interesting was the nuanced portrayal of the heroine, that set her apart from her fellow Philis.

Latvian mezzo Elīna Garanča is an irresistible Dalila, seductively smooth in submission, steely in command and appealing in between. Softly, she could awake anyone’s heart.

But she is no monster, Samson no saint. For the sake of an insult, he has killed her kinsman, and it is only when his body is laid before her that she swears revenge. And at the end, casting aside jewels, she is clearly torn with remorse at his fate while others celebrate his mutilation and humiliation. Appropriately, she appears to be spared as he brings Dagon’s temple crashing down.

The production marked a remarkable debut for South Korean Seokjong Baek, a late replacement in the role and making his first appearance not only at Covent Garden but as a tenor anywhere after switching from baritone.

That may explain the distinctive sound of his voice, which, not lacking in shining top notes, has a remarkably similar tone throughout the range. His stage manner does not match that of Garanča, but he well expresses the anguish of a man torn between desire and faith.

Saint-Saëns originally intended the work as an oratorio, and the Covent Garden choir sing lustily while occasionally being obliged to do a few rudimentary and somewhat rusty dance steps.

The ROH orchestra nicely brings out the different moods that characterise the Israelites and their oppressors, and the disk comes with a bonus track featuring one of conductor Antonio Pappano’s informative introductions to the opera.