In 2004, CBS News published horrifying photographs of the torture of prisoners in the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq by the US Army and the CIA. Once seen, these images of violation, which included physical and sexual abuse, rape and murder, are imprinted in one’s consciousness, not easily erased.

But, one doesn’t need graphic realism to convey horror. Henry Naylor’s The Collector (which won a Scotsman Fringe First Award in 2014 and now, in partnership with Kathryn Barker Productions, is on national tour) requires nothing more than a bare stage, three stools, three light bulbs and a trio of actors to show us how, if not to explain why, ordinary people became monsters.

There is no sound design but Andrew Grange lights director Michael Cabot’s spartan set with economy, precision and relevance, efficiently moving from shadow to exposure, bathing the stage with washes of colour to complement the dramatic mood or the characters’ emotions.

The main auditorium at Greenwich is not an intimate space, but the intensity of Naylor’s form and content persuasively transport us back to 2003: to Mazrat Gaol in Iraq, which is under Allied command. Kasprowicz (William Reay) is the US captain in charge; he tries to introduce enlightened values into the notorious torture house. Foster (Olivia Beardsley), a specialist in interrogation techniques, assists him.

Their stories interweave with that of Zoya (Anna Riding), a young Iraqi woman whose fiancé, Nassir, works as a translator for the Americans, a position he hopes will impress Zoya’s father. Nassir is a pro-Western idealist—a passionate ‘collector’ of American music—for whom war brings both sorrow and hope.

He longs to be able to start a new life with Zoya in a country that is free from Saddam’s tyranny and transformed by the liberal values of the occupiers. It is Nassir’s love of hip-hop that allows Naylor—who, before The Collector, was best known for his writing for television satires such as Spitting Image and Dead Ringers—brings some laughter into the darkness: “If you gave Nassir a dollar, he would come back with 50 Cent.”

Nassir’s optimism proves naïve. When a psychotic prisoner, Faisal, who supports the old regime, recognises him, his safety is threatened and Nassir learns that war brings only a sadism sanctioned and committed by those in authority.

Naylor’s masterstroke is to make Nassir an absent presence. His story is told through the others’ monologues and his literal silence is a powerful metaphor for the vulnerability of his ideals. He and his broken dreams haunt the stage.

Similarly, the voices of both Faisal and the ignorant, brutal interrogator, Valet, are ventriloquized by Foster and Kasprowicz; this results in some biting satire but also disembodies their words, making Foster’s account of their viciousness and evil even more harrowing.

From Animal Farm to Lord of the Flies, from The Lord of the Rings to The Master and Margarita, literature has repeatedly explored the corrupting effect of power. The 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment—alluded to by Naylor—investigated the psychological effects of perceived power. Aiming to test the hypothesis that the innate personality traits of prisoners and guards are the chief cause of abusive conduct in prison, the investigators found that situation rather than internal character shaped behaviour.

Naylor’s characters bear this out. Kasprowicz and Foster start with high-minded ambitions, but the challenges are great. As Kasprowicz resignedly observes: “there were so many rules there were none”. Foster favours psychological techniques over physical intimidation but her words, ‘You can make anyone reveal their true self if you just find the right trigger”, prove tragically ironic.

A suicide- bomber disguised as a prostitute murders an American soldier and a terrible lust for retaliation is unleashed. Naylor skilfully and coolly shows how each individual has their limits; how hatred and fear can dehumanise and lead to acts of unimaginable horror. While Foster rages at her fellow soldiers’ inhumanity, she resists the lure of vengeful viciousness.

In contrast, Kasprowicz becomes frenzied when Foster, whom he loves, is killed by some prisoners, and he seeks retribution by torturing Nassir. By the end of the play, Nassir is dead and so are the liberal values in which he trusted.

The cast spin the verbal web expertly: as the story is passed between them, a hypnotic rhythm is created which draws us, against our will, into the tale. Actions may be few, but the voices have a compelling energy.

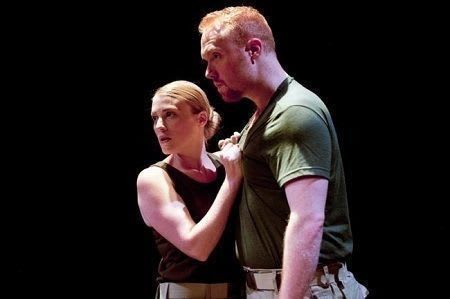

Beardsley conveys Foster’s strength and wilfulness, but also her emotional vulnerability. The bond she builds with Nassir is utterly credible. Reay (reprising his role from the original production) is similarly adept in revealing Kasprowicz’s inner conflict: his passion is both his strength and his fatal flaw. Riding’s Zoya has a strong presence and dignity, and it is troubling to see her diminish in the face of torment and tragedy. All communicate with directness: it is hard to elude their direct gaze.

Naylor’s own experiences of a visit to Bagram Airbase in 2003 inform The Collector. He has followed The Collector with Echoes (2015) and Angel (2016), and the three plays form a trilogy of "Arabian Nightmares", but there is nothing dream-like about The Collector. The play attempts to communicate the truths of conflict, avoiding the sanitisation that can afflict journalism. But Naylor’s shocking reality is all the more affecting for its quietness.