A tenebrous colour palette, black costumes, visceral movement and music that’s a synthesis of analogue, digital and found sound link Scottish Ballet’s double bill, one that needs some reflection: Angelin Preljoçaj’s all male biblical ballet MC 14/22 (Ceci est mon corps) created in 2000 and Crystal Pite’s swarm intelligence Emergence from 2009.

MC 14/22 (Ceci est mon corps) is a fifty-minute-long last supper that mixes Caravaggio and Derek Jarman iconography—homoerotic, ecstatic, violent, cruel and tender—with Pina Bauschian repetitive formation routine.

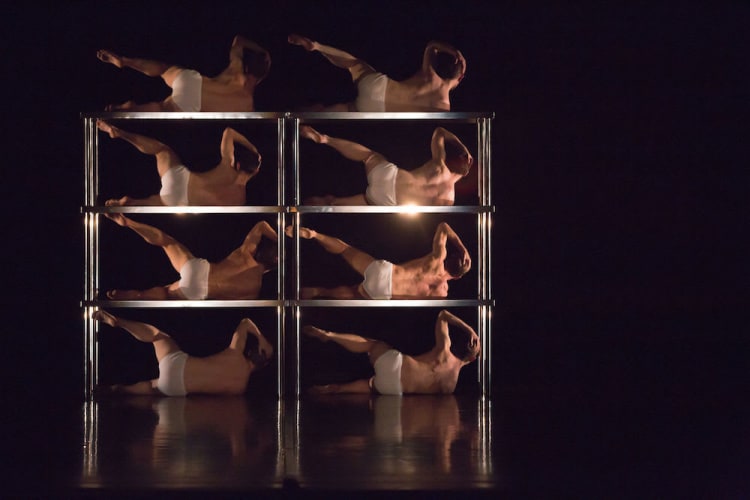

A triptych: to one side a man’s body being washed, to the other a man ripping parcel tape (work that one out), in the centre a stack of display shelves with bodies moving as if in disturbed sleep (a Muybridge motion study?).

Shelves turn into tables, six steel butchers’ counters—morgue slabs. Metallic beats clang, a cacophony of sound, white noise (Tedd Zahmal). Bodies, carcasses, are hurled and held in pietà, tableaux form and reform along the tables now joined in one long familiar trestle.

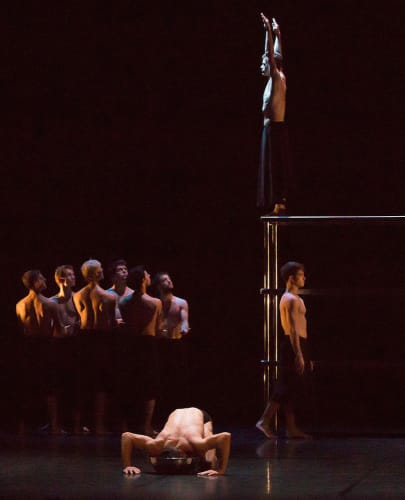

Twelve men in black asymmetrical wraparound skirts (Daniel Jasiak design), their bare torsos sculpted by Patrick Riou’s ruddy lighting into Rodinesque musculature, play out despair, incomprehension, inarticulacy, and lament.

A singing man has his breath constricted, a dancing man is bound in sticky tape—the audience laughs—is it funny, or a nervous release of tension, a need to find some light in the unrelenting darkness—but the impeded men go on, undaunted, overcoming doubt and hesitation.

Religious imagery and metaphor collide and accrue: wrestling embrace, cruciform stance, tenderising flagellation and unified semaphore. Finally trust is attained. Tables now a stepping-stone tower, the disciples climb, fall and are caught by their fellow men.

Trust and strength in unity, safety in numbers: Crystal Pite explores the dynamic mechanics of swarm formation. Emergence was her first commission for the National Ballet of Canada, and her first time working with a large ballet company. Co-opting Thomas D Seeley’s work at Cornell University on swarm intelligence, Pite found her crutch, which has evolved into a signature style, as evidenced by her recent Flight Pattern for the Royal Ballet and Polaris for Sadler’s Wells.

The larger the group on stage, the better for her, here the whole of the Scottish Ballet company, some 36 dancers, male and female. The mass and volume filling the stage make an impact: think precision military parades, Soviet May Day gymnastic displays, bee swarms, insect colonies, starling murmurations, or Swan Lake corps de ballet.

Scottish Ballet’s dancers attack Pite’s choreography with a ferocity and power that blows the cobwebs off Sadler’s Wells. A chorus line of black costumed girls on pointe—pointe noise assimilated and synthesized into Owen Belton’s soundscape—see off presumptuous mates. Ohad Naharin’s choreography momentarily comes to mind.

It’s not only bees—Jay Gower Taylor’s striking set design suggests a nest—but ants and birds, too, with Wayne McGregorish angular arms, disjointed limbs, sway backs, pecking heads, and William Forsythe’s speed and split-second timing, as they mate in duet, buzz in quartet, and boys display in sexy sextet.

Arms like antennae, Sophie Martin, in pas de deux with Evan Loudon, sets the standard in prologue, and the piece grows from there as more and more emerge from a light at the nest’s aperture. Worker bees in black headdresses, chugging sound, bells ringing, voices as one, they invade the stage.

Bethany Kingsley-Garner and Victor Zarallo’s duel duet breaks up the cohort in jazzy fling. Spiky girls, twitching males, reform and colonise the stage. The girls snare the bee man Thomas Edwards. But what about that quartet in black pants—three men and a transgender bee—or is Sophie Martin the topless queen bee?

Twenty-five minutes, half the length of MC 14/22 and all the better for it, Emergence’s stunning stage picture lingers on the retina. Light beckons and the busy bees are gone, back to where they came from.