A labour of love, a personal history, a righting of wrongs (rather late in the day, if I might say so, but better late than never—why didn't Boccadoro write this sooner?): Rudolf Nureyev As I Remember Him describes him as a warm, kind man, with words from those who worked and socialised with him, many he’d treated like a surrogate family. His fiery temper tantrums are there, but these are explained by his perfectionism. This image, of extreme rudeness, is the one the press peddled—I’ve personally been told by one who was there an unrepeatable anecdote—he was every journalist’s dream. She damns the BBC’s “prurient” documentary, the producer knowing nothing about dance (she was asked to help on it). The producer didn't know who Patricia Ruanne was, nor that Fonteyn was dead, he just wanted titillation.

And she has a few bones to pick with the White Crow film—Nureyev was not “the most selfish man I ever met”, quite the contrary. After watching the David Hare scripted film, a ‘friend’ said, “Oh, you've caught him absolutely, except he was a far bigger shit”. This belated book is to correct the lurid, exaggerated accounts. She followed his career for 28 years and knew him personally since 1964. With her, he was not the imperious, arrogant animal he was painted, but had “the soul of a child”. This I buy absolutely looking at his history, his nurture interrupted. He might have been called a highly sensitive person these days… Boccadoro also makes a pilgrimage to St Petersburg after his death to get a sense of his ballet and emotional history. She finds out that he was tried in absentia and given a seven-year sentence.

But he is like a child in the Aladdin’s cave that is the West after the austerity of the Soviet Union and the poverty of his childhood. He wanted it all; he wanted to know it all, greedy for culture, and to pass it on. He was demanding, not least of himself. Art galleries, music (he played the piano, Tchaikovsky, Stravinsky, Prokofiev and Bach were ‘his gods’), languages, books (Goethe quoted at his funeral), kelims (his store of magic carpets), conducting (encouraged by von Karajan and Leonard Bernstein, he studied it at the Juilliard and in Vienna, his innate musicality serving him well)... and an accumulation of fine properties in Paris, London, New York, Monte Carlo, St Barts… did they fill the void in his soul, his much missed mother?

Good to know that Nigel and Maude Lloyd Gosling (she thought him “a truly wonderful boy”), who jointly wrote as Alexander Bland, became his surrogate parents, giving the young man a home in London and helping him to write an autobiography, Nureyev, His Spectacular Early Years, published in 1962. I have it on my shelves, together with Peter Watson’s 1994 A Biography, Julie Kavanagh’s magisterial 2007 tome The Life (Boccadoro has a few bones to pick with its inaccuracies—she likes John Percival’s 1975 Aspects of the Dancer), and more.

Any book on Nureyev, especially with the benefit of hindsight, is welcome. It’s a potpourri of a book, uneven at times, but fascinating, especially his Paris Opera Ballet years, 1983–93, as artistic director when he injected a much needed rigour and vigour into the company, transgressing its rigid hierarchical system. He certainly blew the cobwebs away. These are the years she knows best and it shows. She went through his diaries and contacted all those in his address book for “honest” answers. Many responded, his assistant Genia Polyakov, violinist Ivry Gitlis, designer Nicholas Georgiadis, dancer Charles Jude who was like a son to him, dancer Douce Francois who smuggled Minkus’s original La Bayadère score (badly and illegally photocopied) out of Russia in her knickers. His favourite role had always been Solor. And many more.

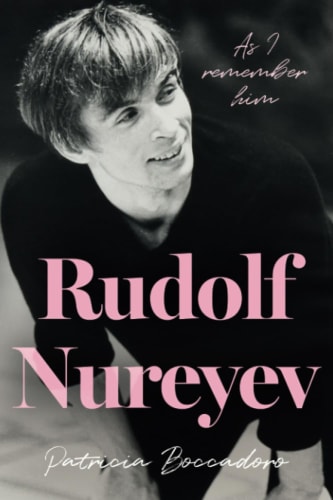

Divided into six chapters of variable length, there is some overlap and rambling repetition—fondly going over it before memory fails, jumping timelines with many asides, as one does with friends. Best of all, they are adorned with many private photos: Boccadoro is sharing her archive and her memories before memory fades—“through the mists of time”. She used to review for Dancing Times, amongst other publications, is a true balletomane and in love with the man. She dedicates the book to her daughter, the “little girl who wanted to marry Rudolf”. He loved children. Confessing to being a Romantic, for Boccadoro, Nureyev is the benchmark, having more charisma, she says, than another famous defector, Baryshnikov, who is mine…

Nureyev (1938—1993) arrived in London in 1962, and Boccadoro starts with his London years 1964–69, his partnership with Margot Fonteyn, when he famously rejuvenated her career. London had seen nothing like this fiery Tartar. At his peak, he was doing an astonishing 250 performances a year. I wish I’d seen him then. He expanded male dancers roles, as well as bringing his Soviet repertoire knowledge to the West. We have his Swan Lake, his Zefferelli influenced Romeo and Juliet, his Sleeping Beauty described in detail. And his Marguerite and Armand with Fonteyn.

Boccadoro is honest about her personal tastes, not always in keeping with critics and reviewers—for instance, she didn't like Roland Petit’s Paradise Lost for Nureyev and Fonteyn, critics did. But she found their Les Sylphides so “excruciatingly beautiful” she couldn't watch it again. The book could just as well be titled “As I Remember Me”… as a camp follower, Nureyev enraptured her. He was “a David”, “his body was absolute perfection”, he “illuminated the score”. Nureyev “gave, gave, and gave”. He paid Fonteyn’s medical and hospital bills. He never got over her death in 1991, two years before his.

At last, we are on home territory—Paris and a history of the Palais Garnier. Nureyev liked to lead a peripatetic life style, performing globally, in Boston in his livestock-littered Don Quixote (later revived for Palais Garnier without the livestock), in Australia… It didn't suit the Royal Opera House, but it was Paris’s gain, where he really rocked the boat, mixing classical with contemporary, Graham and Cunningham, bringing in young choreographers like the then-unknown William Forsythe (in 1987, Guillem performed in his In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated). He brought in Robert Wilson, Maurice Béjart (she doesn't like him, arrogant, trying to go over Nureyev’s head), Roland Petit and more, breaking the barriers. And he laid the base for his Nureyev Foundation.

The oldest ballet company in the world, founded by Louis XIV, Paris Opera Ballet was “stilted and technically poor”. Serge Lifar of Diaghilev’s troupe became its AD from 1929–58. In 1972, we are told the school was reformed by Claude Bessy, but Nureyev had an uphill job. He’s 45 when he arrives in 1983, passionate, raring to go and lead by example. Boccadoro gets quotes from the horses’ mouths. She knew and knows many ‘insiders’. Complaints that he was too good, he’s a culture vulture, ‘his entire life is dance’, he is demanding but patient, authoritative but encouraging, pushing them and himself, he was a perfectionist… He had a temper, was blunt and a hard taskmaster, but he “had so much warmth, so much kindness and generosity”, the Paris company loved him. In his time he spotted Sylvie Guillem and Laurent Hilaire.

Two months after his arrival, he reworked Petipa’s Raymonda for the company. Georgiadis said of him that he was “a perfect gentleman” and “the most intelligent person I have ever met”. Nureyev so loved beauty, he says, he hated an ugly set, and his flashes of temper were soon forgotten. His Paris flat was like Ali Baba’s cave. More descriptions of his ballets follow, his Nutcracker, Swan Lake, a burlesque Cinderella set in Hollywood which divided opinion, Washington Square (a dud), Manfred (disappointing). He liked musical comedy and Fred Astaire.

A patchwork quilt in the stitching of a legacy, which was betrayed in Paris when his contract was not renewed after his valiant work in turning the company around in such a short time. Boccadoro has much to say on that… And finally his death—he was not going to die, he brushed that nonsense aside, and when she last saw him in 1989, he didn't look ill at all (HIV positive since 1984). He didn't want any homage—“hommage … dommage” he said. In 1997, there was an exhibition at the Carnavalet in Paris in which there was a film (amongst others) of him dancing in Petit’s Le Jeune Homme et la Mort with Zizi Jeanmaire—this I’d like to see. There is a Cercle des Amis de Rudolf Nureyev in Paris, and in London 2022 there was a gala in his name. Typos don't spoil the telling, but future editions should check ‘Foyer de la Danse’ on the same page as ‘Foyer de la Dance’.